| lancaster |

| (.470 member) |

| 08/10/11 05:56 AM |

|

|

what do the lee experts think, is it an old sporter?

it seem that the stock have a dark tip.

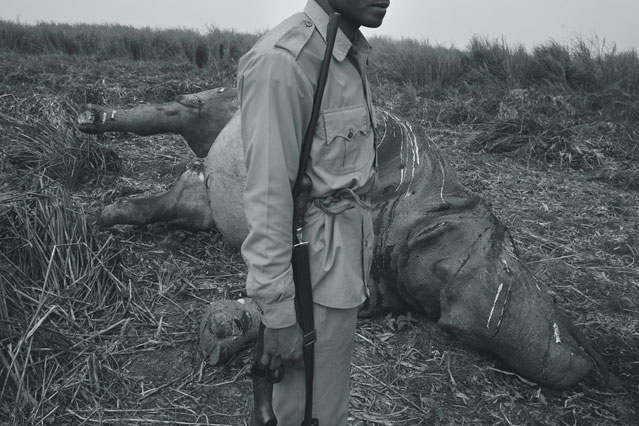

One of Kaziranga National Park's forest guards surveying a poached-rhino carcass.

THE CAREER OF THE NOTORIOUS Indian wildlife poacher Naren Pegu came to an end early on the morning of December 13, 2010, in the Eastern Range of Kaziranga National Park. Tucked away in the northeastern state of Assam, hugging the southern bank of the wide Brahmaputra River, Kaziranga is India’s Serengeti, a mosaic of grass, jungle, and wetlands supporting a staggering amount of biodiversity, including Asia’s highest concentration of endangered one-horned rhinos and Bengal tigers. Since 2005, Pegu had poached about 30 of those rhinos, which live in Kaziranga and almost nowhere else. He’d shoot a rhino, cut off its horn with a machete, and sell it for thousands of dollars in Nagaland, a lawless state that runs along India’s fuzzy border with Myanmar. From there, the horns travel to Myanmar and then to China, where they sell for tens of thousands of dollars a kilo. In powdered form, they cure everything from cataracts to cancer, or so say believers. It’s really just a big fingernail.

Pegu was a member of the Mishing tribe, one of Assam’s many indigenous groups that, like their equivalents everywhere, have lost land and livelihoods. Mishing villages line the park boundary, their inhabitants pressed against it like kids at a candy-store window. If you can’t pay $50 for a jeep safari, you can’t get inside. Growing up here, Pegu learned to sneak past the border; he knew the park like his own backyard. He’d come and go undetected by the forest guards—India’s version of wildlife rangers. Poaching ran in Pegu’s family; his father was a poacher before him.

Most Mishing involved in the trade are content to serve as illegal guides for the bigger regional guns—sharpshooters and brokers from Nagaland—whom they lead in and out of the vast park, taking a small cut. But Naren Pegu was enterprising. He taught himself the rules of the trade, cutting deals in seedy hotels. Learned where to get black-market .303 rifles from the separatists who control the Nagaland hills. He thought big. Typically, poachers blow any money they come into, but not Pegu: he’d saved enough to invest in three vehicles, a big house, even a plot of land, where he was starting his own tea garden in some sort of psychological stab at legitimacy. While Pegu was bringing down more than $20,000 per year through poaching, his Mishing relations scrabbled to earn $200 a year in the rice paddies.

Pegu had every right to feel cocky as he and an accomplice slipped into Kaziranga on the evening of December 12, waiting out the night munching on rotis and precooked rice; a fire would have given them away. At dawn, rhinos scatter across Kaziranga to feed on the rich grasslands, and Pegu was ready. He came upon a mother rhino feeding with her calf. Got out his rifle. Shooting a rhino is like shooting a barn: when you take aim, they stop and stare, deciding whether to charge. Pegu shot the mother dead, hacked off her horn, and left the baby standing there. The park border, his village, and a payday in Nagaland were not far away.

Pegu should have been home free. He knew the landscape, and Kaziranga employs only about 500 forest guards to cover more than 300 square miles of tall grass and jungle—on foot. What were their chances of finding him? Yet, unbeknownst to Pegu, before he even fired his shot three forest guards had entered the area, searching for him. As soon as he fired, they closed on the spot. Unlike most guards in most parks in India, they were armed. And they had license to kill.

Pegu saw the guards first and opened fire. Missed. The guards took cover. As the shooting continued, one guard calmly raised his antique .303 Lee Enfield rifle to his shoulder, lined up Pegu in his sights, and blew his head off.

Pegu’s accomplice was shot in the hip by another guard. An hour later, he, too, had died “from his injuries,” according to the park’s report. Pictures from that day show the two men lying on the forest floor. The accomplice has dried black blood around his eyes, nose, and ears. Pegu’s head is split open like a watermelon.

Krishna Deori, the director of Kaziranga’s Eastern Range, one of the park’s four divisions, proudly shows me the gruesome pictures when I visit his office, a concrete bungalow beside the park entrance, in April. “I almost gave up!” he says. “I was ready to leave this place because of him.” Then, in a red UNITED COLORS OF BENETTON shirt, Deori models for my camera with rifles seized from poachers. I try to envision a ranger in the U.S. doing the same. But nothing in Kaziranga is like anything in the U.S. There’s the superdense concentration of tigers, rhinos, and elephants—and the fact that they’re thriving. The sheer value of that wildlife on the black market. The grinding poverty of the surrounding villages. And the tsunami of money and demand pouring out of China. Kaziranga is an ark bobbing upon a frothing sea of humanity. Yet somehow it keeps on floating.

http://www.outsideonline.com/outdoor-adventure/nature/Number-One-With-a-Bullet.html?page=1