NitroX

|

| (.700 member) |

| 21/03/14 03:36 AM |

|

|

|

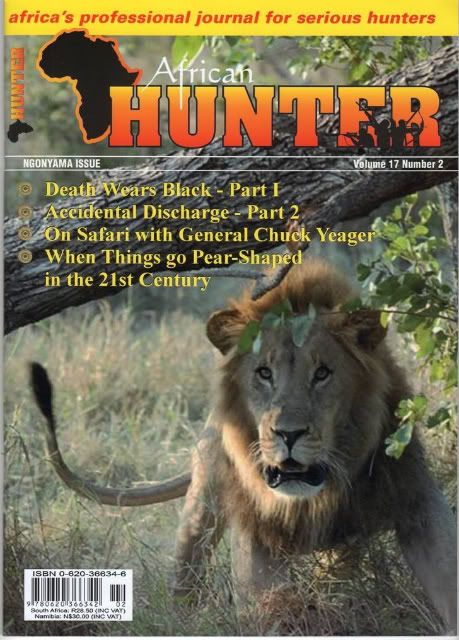

My story from our Zimbabwe hunt in 2008 is currently being serialized in African Hunter Magazine. The first issue came out around two months ago and so the second installment should be here any day now.

All total its going to take about 5 or 6 issues to print the whole thing, which means almost a year from start to finish, but for members only, here is the complete and un-edited version.

Hope you like it.

-------------------------------------------------

“If he comes now, I must be quiet inside and put it down his nose as he comes with his head out. He will have to put the head down to hook, like any bull, and that will uncover the old place the boys wet their knuckles on and I will get one in there…”

Ernest Hemingway, Green Hills of Africa

Part I

Africa calls to me

From just behind me Richard said, “If he gets up you shoot him.” And I thought, “There’s no way he’ll ever get up again.“ But there really was no time to think about it, and he did get up, and when he did come, it was in a very matter-of-fact way. And there was no rage in his eyes that I could see, no slowing down of time, no hatred, and certainly no question about his intentions. It was simply a matter of getting up on his three good legs and turning, coming to kill me, to put an end to this predator that had somehow taken him by surprise and that now had the audacity to approach him.

That was on day six of a ten-day hunt in the Chete safari area of Zimbabwe with Richard Cooke, (Richard Cooke Safaris, Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe) accompanied by his wife Belinda and my wife Alicia, and we had hunted hard for five days before we even saw a bull. Tracks, or spoor as they say in Africa, and other signs were there of course, but not in any quantity. Long before I even arrived in Zimbabwe Richard and I had agreed that in our search for an old Dugga-Boy we were going to ignore all herds, and to that end we had stopped only once to look for evidence of a bull in some very fresh spoor of a small herd, the possibility quickly dismissed by our trackers Joseph and Silas. It was the old solitary bulls that we were after. They would be alone, or in very small groups, making it that much more difficult to find them.

So having traveled from San Antonio to Washington DC to Johannesburg, where we spent the night at the Afton Guest House after having dinner at Tribes at the Emperor’s Palace in Pretoria, to Victoria Falls the next morning and then to a camp called Sijarira by charter plane and finally by boat to the Chete Gorge Camp, I was on my third African safari, my second visit to Zimbabwe, and my first hunt there in the summer of 2008.

Traveling up the lake, I pondered what it had taken to get here. Not merely the travel to our current physical location, though that was an adventure itself, but to realize the consummation of childhood dreams of hunting one of the most dangerous game animals in one of the truly wild places in Africa. It all started with an elementary school library book that had a picture of some Cape Buffalo, appearing to me at the time so terribly vicious. From that book I continued with Beard, Hemingway, Capstick, and others. Capstick and Hemingway were always my favorites, and I always imagined myself being there one day and experiencing the same fantastic encounters. Hemingway was descriptive, Ruark told tales of what the hunt meant to him, and Capstick made it all sound exciting. I wanted all of the above.

My first view of Africa had been the crescent shape of the coastline at Dakar in Senegal, illuminated by the streetlights against the darkness of the night, two years prior in 2006. South African Airways sometimes stops in Senegal on the way to Johannesburg, where I was headed on my first safari. That trip had included a three-day excursion to Victoria Falls. We had hunted in the Limpopo province, and while I love the Bushveld of South Africa, I remember thinking at the time that Africa did not look like the Africa that existed in my mind until we were motoring down the Zambezi on a sunset cruise to see the falls. This vision was of course the fault of the writers, and now, traveling up the lake, with the sunlight shining on the water, I was once again in that Africa, but now I was there to hunt. Having met Richard Cooke at the Dallas Safari Club convention two or three years prior, I was originally hesitant to hunt Zimbabwe based on fears of the country’s political situation, and so I went to South Africa, but when we visited Victoria Falls I knew that I had found what I had been seeking. When I first met Richard, I had immediately liked him. His demeanor was to my preference, his photos and claims of success were impressive while not excessive, and by some coincidence we shared the same birthday, curiously enough along with Zimbabwean Dictator Robert Mugabe. This certainly could not be construed to actually mean anything but it was funny to us. Long-past fatherly advice lingered in my head about how I should have gone with my first inclination, and so at our next meeting at the convention in Dallas I booked a hunt for June of 2008. It had been at least five years since we had first met, but Richard later told me that he somehow knew that we would be hunting together one day. That day having arrived, here I was, watching fish eagles, pods of hippos, and palm trees and palmetto scrub lining the banks, crossing the middle of the sun-dappled Lake Kariba to the Chete Gorge camp. Alicia and I had met Belinda at the Victoria Falls Airport, and we flew by charter to Sijarira on what had to have been the windiest day of the year. We could not fly to Chete directly because even though the Chete camp has a runway of its’ own it was unusable and had been condemned. A bush runway that gets condemned must surely be in some significant state of disrepair, but this was not a problem as the boat ride in the Pelican launch simply added more to our excitement and adventure. To start in such a manner only added to my confidence that this experience was surely to be different, the bar having been set very high by the aforementioned authors.

Motoring along with the sunlight sparkling on the water, I looked behind me at Alicia. She was sitting with Belinda and holding on to her hat, her smile beaming at me. The plane ride in the Cessna had been rough enough, and now she was taking a beating from the lake, but I knew that she was as happy as I was. Passing the sandy beach on the right we finally entered the gorge, where we could see high above us the chalets of the camp. We were in the shade of the gorge while above us the camp was illuminated by the setting sun, and in an idyllic scene, we turned to the right into a cove, onto sheltered water that was as smooth as glass. Brasho our boat driver skillfully managed the power so we created only the slightest wake as we entered this calm and peaceful setting, the motor rumbling very quietly, and rounding the corner there was Richard, standing on the bank waiting for us. In my mind I can still see the soft light from the setting sun on his face, and the happiness in Belinda’s as they embraced. I helped Alicia off of the boat and after greetings we were immediately introduced to Joseph and Silas and several of the other camp staff. With smiles beaming we shook hands in the African three-step method, greeted in such a way that can only be done with absolute sincerity. Immediately the staff then scrambled after our luggage, refusing to allow us to help. We were all very happy to be together after so much time planning and waiting, and as one is apt to be at the end of such a long journey.

I don’t remember everything that was said, but I remember the feelings of relief and excitement and anticipation. We stretched and flexed out tired bodies, and driving up the hill to the camp, we saw the cluster of buildings, and a sign painted on a rock that merely said “Chete.” This was to be our home for the next ten days. The chalets were made of stone with thatched roofs, rounded at the ends and with a screened open front that faced the lake. Behind the chalets was a smaller building that looked like a smokehouse and when I went to examine it Richard told me it was the water heater, with a fire kept burning at all times. The water was pumped up from the lake into a cistern above camp during hours that the camp generator would run, and from there gravity fed water down to the water heater, kitchen, and chalets. The camp staff delivered our bags to our chalet, refusing to allow us to help, and with our gear well tended, and looking around and taking in the sights, smells, and sounds of Africa, we happily ambled over to the open dining area, where Richard was reaching into the cooler box.

“Castle or Zambezi?” He asked me.

“Zambezi of course,” I responded, already smiling at the thought and nodding towards the lake.

“Appropriate enough” said Richard, “Though our stock of Zambezi is limited. You’ll have to switch to Castle in a day or so.” And as he spoke he pulled out two bottles, and turning one upside down, he deftly flipped off the top of the other, somehow not removing the top of the inverted bottle, and handed me my first one in country in two years.

“To the mighty Zambezi” we toasted, and the beer went down in a rush of cold like the mighty falls that are the hallmark of the river.

“Caste is generally preferred you know.” Said Richard smiling.

“Not by me.” I responded.

Holding the green bottle up to the light of the setting sun and examining the label, I continued.

“If we are on the Zambezi then we should drink Zambezi.” I declared.

Richard laughed and took another drink of his Castle, and I thought I heard him say something about Americans. We were all full of happiness, excitement, and anticipation.

That night, we met the rest of the camp staff, including Dustin the apprentice PH, Sylvester the chef, who was to leave in a day or so due to illness, and Mkusana the headwaiter. Mkusana had a smile as bright as the sun itself, and we soon came to be very fond of him. Dustin showed us around camp and explained the workings of the lights and the water in the chalet.

“Don’t come out at night, whatever you do,” said Dustin.

“OK,” I said.

“I wasn’t planning on it,” said Alicia. Her eyes wide and her inflection one of friendly indignation.

“No normally it’s very safe,” laughed Dustin,

“But there’s been a hippo coming into camp every night.”

Alicia’s eyes were wider now.

“He comes in to eat the grass,” Dustin explained. “He’s no trouble so long as you stay inside. He comes in late after the generator is shut off, and leaves well before the morning. He knows when to leave.”

So this was Africa as it should be. Thatched roofs, wild animals in camp, sleeping under a mosquito net, or bar, as they say. I always said I sleep best under the Southern Cross. “Have to add thatched roof and mosquito bar to that list.” I thought.

At about two in the morning I awoke to the sounds of someone dragging a broom across the grass outside. I pondered the source of the noise for only a minute or so, and very quietly, taking my red flashlight, I went to the screened front, and there he was, not 30 feet away, grazing happily. Quietly, I awoke Alicia so she could see him as well. Yes, I was right, this is how it should be. This is where I should be.

The next morning we were up early, and after breakfast we were all ready to start. For all the enjoyment, the people, the cold beer, the animals, the sights, smells, sounds, and other wonderful things that are Africa, I had come to Zimbabwe in search of syncerus caffer, the African Cape or Southern Buffalo. I had wanted to hunt in a manner befitting of the game and times long past, with no fences and on foot and here in Zimbabwe I was not to be disappointed.

In the Chete safari area, which is an enormous expanse of scrub, Mopane and Combretum, natural springs, and huge Baobabs, roads are minimal, and so the well-written-of axiom of driving until you find tracks was somewhat ignored. We drove some roads of course, but mostly so that Richard could mark out a few points for reference on his GPS, or for us to reach a starting point for the day. True landmarks along the roads seemed even more rare than the roads themselves. There was the condemned airstrip close to the camp, and one major intersection that we would pass daily, where the road split and went to Binga, Siantula, or the Chete camp, with of all things a sign marking the intersection.

Most days we only drove in the mornings from camp to get out to the areas where we wanted start the day, and from there we would walk. With so much space in Chete and in that space dozens of springs providing water, a buffalo might live the better part of his life and never have to cross a road. Along with the lake there seemed to be water available everywhere, and so over the next few days we walked, and climbed, up hill and down, following game trails and sand rivers, in search of buffalo spoor to follow. There were many tracks at the standing water in the riverbeds, and at the springs. In fact, there seemed to be tracks everywhere, but we were to actually see very few animals. The hunting was hard and most tracks, if not nearly all, were dismissed as too old, but I felt no disappointment because I was back in Africa, and it seemed at first that we had plenty of time.

Part II

The Hunt

On the first day, we started our walk near the shore of Lake Kariba, near one of the inlets where the water came in and was according to Richard very high for this time of year. Belinda and Alicia were with us, the four of us very happy to be out together. From the road we had seen a large bull hippo on the shore moving out of sight around a bend, and we set off hoping to get some pictures of him entering the water if we could get close enough before he spooked. The truck was sent around to a meeting point and we did not know then that it would be about 5 hours before we made it there. We eventually did catch up with the hippo, and even though he was already in the water, we did get some good pictures of him exhibiting some sort of displaying behavior directed at a large crocodile.

On we went, sometimes following the shoreline closely, sometimes moving slightly inland to take advantage of the terrain or to shorten our path by skirting over a peninsula. We saw a very impressive kudu bull in the trees, and some impalas in a meadow by the lake. The impala were in high grass and the meadow was really an extension of an inlet where the water would come in and the grass looked very lush, and mixed into the grass were longer stems with yellow flowers on the tops. We decided that since the impala looked so peaceful and because the grass suggested it was probably muddy in there, we should skirt around to the left, going up and over a small hill, back into the mopane scrub where we thought we would come back down to the shoreline on the other side, but our track took us higher than we thought, and we found ourselves higher up, moving through a mixture of green and brown mopane, with the occasional Baobab mixed in, but we found no buffalo tracks, and for some reason we never made it back to the shoreline. The sun was getting warmer, and our senses that were becoming slightly dulled were suddenly brought back to life as Richard stopped and held up his hand. Directly in front of us, no more than 50 yards ahead, was a pair of bull elephants. I could not see them at first, and standing still they looked like large boulders, but the slow flap of an ear finally gave away their presence, and then actual movement defined them, and I smiled as Alicia grew wide-eyed and moved closer to me. We slowly closed ranks so we could whisper to each other, and Richard said they showed better than average ivory for Chete.

“Too bad we are not hunting elephants,” he said smiling. “Isn’t that always the way it is. If we were after ele’s the buffalo would be thick.”

We enjoyed watching the two bulls for a while, taking video and some photos and the click of a camera seems unbelievably loud in such a situation. They were slowly feeding, and seemed unaware of our presence. The wind was right, but suddenly one of the bulls started moving to the right, angling in our direction. If he maintained his course he would pass to our right at perhaps thirty yards distance. Alicia was getting nervous and I could feel her hand on my back as she moved in closer to me.

“Watch what happens when he crosses our track,” said Richard.

“Why,” whispered Alicia nervously, “what’s going to happen?”

“You’ll see,” said Richard.

His smile and his confidence, as well as her understanding of his level of experience, should have calmed her, but it didn’t, and she pressed even closer in to me.

“Hold still!” I hissed, trying not to sound like a parent speaking to a child.

Suddenly the elephant stopped. He had reached the spot in the open where we had crossed, and his trunk was moving across the ground sniffing.

“You see,” whispered Richard, “he knows exactly where we crossed, and he can probably estimate about how long ago.”

Seemingly satisfied, the elephant did a sharp turn to the left, and slowly ambled off in to the brush, never having crossed our track.

Smiling at what we had seen, we all relaxed, Alicia with some relief, and we returned our attention to the other bull, which had not moved from his original spot, but now began making his way to the right towards the lake. This was the path that we had hoped to take, and so we now began to follow him. As we walked along, Alicia was still undecided about her desire to play with wild elephants, but she was slowly becoming more confident. We had to walk quickly even though the bull was moving relatively slowly, and we kept directly behind him but very close. Like a submarine unable to detect anything in its baffles, he never knew we were there, and he might never have known if we hadn’t spooked a pair of Francolin off the side of the path. They cackled as they rose into the air, and the elephant stopped and turned slightly to his left, eyeing us without concern. We froze in our tracks. We were very close, and his odor was very strong with the wind in our faces, but eventually he moved off to the right of the path, heading for a shady area down by the lake. We finally let him go, taking his picture as he departed.

While the elephant was headed for the shade, we on the other hand, remained on the path out in the sun, and it was very warm. We were continuing our track around the perimeter of the lake and moving across a hillside at one point, when there was suddenly a panicked rustling in some brush to our right and Richard and I both quickly dropped our rifles off of our shoulders and were both standing ready to fire when we saw the steenbok break clear of the brush and run down and across the draw. We looked at each other and laughed at so much noise coming from such a small animal. Little did we know that we would repeat this scenario in a few days, but with something much larger.

And so on we went until we came up one of many draws and there was the truck and Joseph was sitting in the sunshine and the water was already boiling for tea. It was late in the afternoon by the time we finished our lunch, and we decided that this being our first day we would go back to camp. On our way we drove, quite unexpectedly, right up to a herd of elephants next to the road. The sun was down but it was not yet dark and we continued moving slowly because I was trying to take a picture. The long lens was on the camera and I was contemplating the difficulty of changing the lens when I saw a very small calf run by not 10 feet from the truck. “That’s can’t be good.” I thought to myself, and it was about that time that we heard the trumpeting of one of the cows and saw her crashing towards us through the trees. I could see Richard smiling in the mirror as he quickly sped up, and I heard Shadrick the game scout who was standing in the back of the truck asking very politely to “Please go - she is coming!” as he pulled the charging handle on his battered service rifle. We got away well enough, and while we had not seen so much as a single buffalo track it was a fantastic ending to a spectacular day.

Drinks and dinner in camp, followed of course by the obligatory tea, served less to provide nourishment, though we were very hungry, but more of a way of facilitating a sort of mental retreat by turning our attention to the basics of survival, and therefore minimizing any additional external stimulation, and to allow for dissemination all of the sights and sounds taken in during the day. You might think that there are limits to what can be absorbed, and after such a day what more could a person reasonably expect, but in Africa there is always more, and sitting in front of the soft glow of the firelight we could see the lights of the kapinta boats out on the lake, and the stars shining down on us through the canopy of the trees, and when the conversation was over we all sat there for some time, and the only sounds were the crackling of the fire, and the gentle lapping of the waves far below in the gorge.

Sound is an interesting part of any African experience, with the cries of the fish eagles over the lake and the haunting yelp of a hyena at midnight, but the call of the Emerald Spotted Dove is surely the sound of buffalo hunting. Having first heard it in 2006 in South Africa, it remains indelibly imprinted in my memory. Whenever I feel the need to actually hear the call between trips, I can usually pick it up on the streaming feed from the AFRICAM website, but most days I can hear it in my head as if I were there, and in a quiet moment if I close my eyes I can see the Mopane leaves rustling in the breeze, and the tracks in the sandy soil, and feel the sun on my face, and always of course, hear the sound of the birds. Richard and Belinda were constantly marking the names of birds for their life lists. Everyday we saw many doves, storks, fish eagles, hammerkopfs, geese, ducks, falcons and other raptors, bee-eaters, and my favorite, the kingfishers. We saw hippos and crocodiles, lots of elephants, impala, duikers, kudu and hyenas, but no buffalo.

While hunting in the Zambezi Valley it might be said that while you constantly hear the doves calling you never seem to see them, and this I think is mostly true, but early that first day Richard actually spotted one on it’s nest, in a small Mopane at shoulder height to the right of our track. The bird held tight while we examined it from no more than three feet away, the iridescent green patches that are the source of it’s name showing brightly in the sun, but when we turned to resume our walk it flew, and so we turned back to take a picture of the nest and the next generation in the form of two small white eggs.

Another observation on sound, which I believe bears mentioning, is the sound of the voices of the African trackers. It must be the hectic lives that Americans lead, because people in Africa by comparison seem to speak very softly by comparison, and yet their voices are deep and quiet and very clear. A routine day starts early, with breakfast of coffee, and eggs fried in the center of a piece of toast, with perhaps mushrooms or tomato on the side. Enough protein to keep you going, enough bread to fill you up, and just enough butter to make it truly delicious. The early morning in Africa is always a magical time filled with anticipation for the day to come, and walking from the chalet to the dining area in the pre-dawn darkness, the first hint of sunrise very low on the horizon, barely discernable through the trees, the quiet and the stillness were never disturbed, but slightly enhanced by the sounds from the kitchen, and the soft low voices of the African staff preparing the breakfast and the other provisions for the day. Assuming no success while hunting the morning, a mid-day break for a proper bush lunch and rest is the standard routine. At any bush lunch or time spent resting while hunting, the trackers and the game scout will move off slightly from the main party, and as we would eat and then rest, you could always hear their voices, talking quietly amongst themselves. During these times, while resting or even sleeping in the shade of the trees, an unbelievable relaxation can settle over you, and your mind falls at ease listening to the breeze through the treetops, perhaps the birds, the occasional call of a baboon, and the soft low sounds of the voices of the trackers.

The next day we were to take another route, but driving past the condemned airstrip, in the darkness of the early morning, we spotted a leopard running across the road in the headlights. Richard stopped the truck and then he and the others got out and were examining the road, having seen what I did not. The tracks clearly showing where a herd of buffalo had crossed that morning. I got out as well and while they were looking at the road, I noticed something.

“There’s something in the road,” I told Richard. “A hundred meters out.”

It was not the leopard but three large hyenas. With binoculars we could see at least three but we could hear more of them, and now some considerable noise from the scrub to the left. We watched them for a while, and then, moving up in the truck, we could see the hyenas tearing at something before reluctantly giving way to us, and moving to the left in the Mopane, we found a still warm but very dead buffalo calf.

What must have happened, in the half hour at most before our arrival, was that the herd crossed the road, the leopard killed the calf, the hyenas were closing in, and the truck was the last straw in the leopard’s decision to abandon its kill. The opportunistic hyenas had then proceeded to take as much as they could before they too abandoned the kill. Before we left, we put the calf in a tree and covered it with branches, hoping that the leopard would return later. If it did, we would construct a blind and hope for some photo opportunities.

Returning to the original agenda, we drove to our planned destination, and started the day’s walk at a spring where we followed the path of the water as it moved through some beautiful low country, where the dew reflected in the morning sunlight like a million diamonds in the grass, and the suns rays cascaded down through the treetops and shone in beams in the misty air. There was a large Hamerkopf nest in the tree where the spring emerged, and we stayed on a game trail under the trees following the path of the water. It was very different from the dry and dusty Mopane scrub of the previous day.

At one point the path we were on disappeared as the streambed became deeper and there were many large rocks strewn around. The rocks were better described as boulders, and they were dark and smooth, and we hopped from one to the next as we moved over spots where the deeper pools held still water. We could move very quietly over the rocks, and while most of the stream was running, the small rivulets made only the slightest sound as the water cascaded over the smaller rocks and through the shallow areas. At one point, I stopped and turned back to purposely take in and remember the beauty of the path we had just taken. It was certainly a road less traveled. Richard turned around and looking at me he inquired without words what I was doing, and I indicated with a nod of my head.

“Yes,” said Richard, “This is a special place.”

And we turned back down the trail, leaving behind the boulders, and the deep pools, and the tiny waterfalls, but they all went with me in my mind, so that now they will exist forever in two places.

The stream eventually widened again, and then slowly disappeared into the rocks, and the path we followed diverted into a larger channel, that was mostly a dry sandy riverbed. On the paths there were many leopard tracks and whenever we stopped Richard would point out details in the spoor or possibly trees that would make ideal baiting sights based on prevailing wind and the direction of the sunrise or sunset. I was absorbing the lessons as well as the sights and sounds of Africa, but again there were no buffalo. Leaving the sand river, we found some sign, mixed with large quantities of elephant droppings, in some broken jesse where large green bushes that Richard called a type of Combretum were interspersed with meandering open areas. We moved very quietly, and very cautiously as any one of the bushes could easily hide the odd buffalo or elephant. In these areas the group spread out a bit to look for fresh sign, but I stayed close to Richard without being told to do so. It was a very enjoyable way to hunt, stepping quietly and moving very slowly and deliberately, and I watched the trackers and Richard at their work, hoping to learn as we went along.

That day we stopped sometime after noon for lunch in the bush, and tea of course, then resting, and taking up the track again in the afternoon, or rather the search for tracks, again we found nothing that held any promise. It was as if the buffalo had simply disappeared, and Richard speculated that there must be some sort of local seasonal migration. Earlier in the year Richard had been in Chete and had sent me a message that the place was crawling with buffalo, and so this is not what either he or I had expected. I was not yet frustrated, but I could not help thinking about the time I hunted elk in Colorado, near Cripple Creek, for nine days and I never even saw a bull. In this manner we were to continue for three more days.

It was on the third day that we actually got on our first viable spoor. From the very fresh tracks we decided that they were from two bulls that Shadrick knew of that had taken up residence in a block near the camp, between the main road by the condemned airstrip and the road that led to the parks office. Joseph thought from the sign that they were returning from a night spent in the lower areas near the lake and that they would look for their spot to bed down at the top of the hill where the wind and their position would provide them the advantage. We set off after them and we followed them up a slight incline. However, it soon became apparent that Joseph had been right and the wind was squarely at our backs. We continued slowly and as quietly as possible, and at first I found the tracks relatively easy to follow, but I knew that it was not the tracking but the approach that would be difficult. Concentrating on this and looking ahead, I was no longer trying to follow the spoor, but when Joseph threw the stem of grass he had been carrying in a spear-like fashion that expressed great frustration I knew what had happened and you could see it in the splattering of dung and the sand thrown from the hoof prints. They had obviously caught our scent, or possibly heard us, and had continued up the hill, now moving at speed to get away.

Knowing that the parks road was only about a mile ahead, we continued on the spoor, and our plan was to follow them to the road and if they had not already done so, push them across into the next block towards the lake. Either way, we intended to stop at that point and have lunch, and then rest for a while, allowing them time to settle down. From the road we would then continue on the spoor and try to catch them in the evening light, when they would be feeding and their heads would be down. In the evening the wind would settle and if they did raise their heads we would be approaching them not with the sun behind us, which would be ideal, but to the northwest, which would be close enough. It was a near-perfect plan, except of course, for the fact that we were chasing two very wily old bulls. The sign, as before, was very easy to read, and it clearly told the story of how we had been outsmarted. One hundred meters short of the road, they turned 90 degrees to the right, ran parallel for about another 150 meters, then turned again 90 degrees to the right, and ran right back down the hill we had just spent four hours climbing. It was obvious that they, now on high alert, had no intention of leaving their comfort zone, where they seemed to hold every advantage, and so we gave it up. We had never seen or even heard them.

Day four was the same, only more so. Alicia and Belinda stayed in camp that day, and so we drove to another area to the east. Climbing in the Land Rover over an expanse of hills, we could just see the sunlight was sparkling on the lake in the distance behind us, and we turned and then came down a very steep hill, where the road was very rough and strewn with rocks, and we took in the sight of the expansive valley that was our destination. We did not know it at the time, but we came to call this area “The Valley of the Bulls” because we were soon to find that there was sign everywhere. Throughout our time in Chete we had fun labeling the places we went, bestowing names like The Valley of the Bulls, Leopard Valley, and Vundu Point. It gave identity to the areas and personalized them, and the names now serve my memory as much as the sounds of the Fish Eagles, or the colors of the Bee Eaters. We finally arrived at our stopping, or starting point that is, by a sand river tributary of the Senkwe, and we parked near a very large Baobab, standing sentinel in the middle of the valley. After the obligatory brew-up we spread out to look for fresh sign. We had driven a considerable distance in the Land Rover just to get there, but we did not hurry, the day ahead seeming and ultimately proving to be a long one.

The Valley of the Bulls came to be so named because what we found was not tracks or indications of large herds, but many large single and double tracks, and large droppings everywhere, some fresh, and many older. The old bulls were surely in this area, but they held almost every advantage, and we would have to work very hard to find them. The sun was hot early that day, and while it was not long before we picked up what looked like some promising tracks, I should have known that we would be on them for several hours. From the riverbed we skirted around the base of a hill, then losing the track and separating, Richard and I went straight up while Silas and Shadrick continued around the base of the hill. Up the hill on the sunny side, rifles slung so we could grab hold of trees as we ascended towards the top, I was thinking that the terrain was more suitable for klipspringers than buffalo, but there at the top, with no sign of where it had come from, was a large fresh dropping, and following the tracks that led away, we circled about three quarters of the way around the top of the hill, then back down, finishing and meeting up with the trackers at nearly the same spot where we had separated an hour before. We were certainly paying the price in miles walked. I was scratched and bleeding from numerous encounters with thorns, but Richard’s experience in the bush left him not quite so tattered. He knew not to pull when he felt something restraining him, where as I in my inexperience wanted to charge through the bush like the bulls we were after.

“No matter,” I thought to myself. “Except that Harry in Snows of Kilimanjaro started out with a scratch as I recall.”

When the time came, if it came, I knew I would feel that I had hunted fairly. It was hard work but not unbearable. The real effort was in maintaining my focus and staving off the frustration that was coming from so much time and so many miles without even seeing a bull, or even a herd of cows for that matter. The irony would come in how we found our first bull, after so much time spent on their trail, but that would not be for another day.

Discussing our situation after we had met up again, and interpreting the signs, Silas explained that the bulls had run down the hillside, either having heard us or perhaps having picked up our scent. They had split the space between us, and running down and across the valley they appeared headed for the next hill, which was even larger than the one we had just left. From our position, we could see down the hill we were on and into the valley to the left and right. The country was mostly a mix of Mopane and other larger trees, with Baobabs scattered about as well, all interspersed with small open areas. We decided that we would sit in the shade and glass, or simply watch and try to pick up some movement, but after half an hour we had seen nothing, and with no better option presenting itself, we took up the track again.

In soft sand and dirt tracking buffalo is relatively easy. It was through the tall grass and leaf litter and more grass, and even over rock, that the trackers showed their skill. Some of that skill seemed to be the ability to scrutinize the terrain and know the path that the buffalo had taken even when no sign was available. I observed that when we would lose the track, there was no hint of the slightest concern, as it was only a matter of few minutes and moving forward slowly a few yards until we found it again. At first I would stand still when this happened, worried that by trying to help, the chance of my spoiling the track was greater than that of my actually finding it again, but by about the third day I had developed enough confidence that I would join in these efforts, and thereafter on at least three occasions I actually was the one to pick up the track, signaling to the others in the same low soft whistle that they used, and waving my hand as they did with my fingers pointed downward to show the direction of the spoor.

We were hunting very well together now, moving quietly and communicating with minimal if any verbalization. Everyday we would travel in a loose formation through the bush, and when we would come to a more open area we would fan out to cover more ground in search of spoor, closing up our formation when the cover became thick again. The mornings were cool but as soon as the morning shade gave way to the sunshine it quickly became hot, and so we would stop every hour or so and take a drink of water, all of our movements and actions performed silently, becoming routine, as if we had been together engaged in such pursuits for years.

Completing our circle, we returned to the truck once more, and with plenty of light remaining, a quick re-stock of water was all we needed before setting out again another direction. Moving east, across a large flat area, after a mile or so we came to another hill, bigger than the ones from the morning. Climbing was difficult, but we went up and over and across the sunny face, before descending back down once again into the open flat country. On a rock by the path lay a skull from a bull kudu, well bleached in the sun, like some reminder that death was a significant part of life in the Valley of the Bulls. It could have easily been framed with a note to “Abandon all hope…” Walking a bit more, in the flat part of the center of the valley we soon found ourselves realizing that we had entered a grove of sorts, where a group of large straight trees grew up very high, with only dry grass and little or no undergrowth, and the entire area having a very cathedral-like aura about it. The yellow grass was cropped very short, and there were large piles of buffalo droppings everywhere. The sign did not indicate a herd. There were no small tracks and no small droppings. Just large excremental evidence, and many large tracks suggesting we were in some sort of secret lair. We walked quietly; nervously looking around, and I had the feeling as if we were in someone’s house without their permission. Perhaps we should have heeded the kudu’s warning. The bulls were no doubt here somewhere, if only we could find them.

Leaving the cathedral, we made our way west and back to the Land Rover without speaking. Hot and tired, we ate cold leftover Boerwurst, and drank the last of the Cokes. There was only Castle beer, but by then I was too tired to complain.

On the fifth day, we returned to the Valley of the Bulls, and once again we drove down the steep road, taking in the majestic view that it offered, and made our way down and into the middle of the valley, parking near the large Baobab from the day before, and again we started from there. On this day, Alicia and Belinda had joined us, but by mid morning they and Dustin separated from us. We had made one pass through and area and walked for perhaps a mile or two up some riverbeds. We had found some camp sights where fish poachers had been drying their catch. The sticks for the racks were stacked and suggested that someone was planning on returning in the future, and from what we saw on the ground it looked like they had been very successful in their endeavors. Circling back to the Land Rover we stopped for requisite brew up, and then Alicia, Belinda, and Dustin were going to drive to an area where we would set up a camp and wait for us to join them for lunch. Setting off again, Richard, Joseph, Shadrick and I again found ourselves moving up a dry riverbed, where the soft sand showed lots of tracks that were fairly hard to read. When we came to a bend in the river, there was still a small amount of water, and the saturated sand immediately adjacent to the pool made the tracks much easier to read, and there in front of us were the very large and very fresh hoof prints of a lone buffalo bull. The edges of the tracks were sharply cut in the wet sand, and the sand that had been tossed up onto the surface seemed to still retain moisture.

We stood there as Richard and Joseph discussed the sign, clearly made sometime that morning, but their individual interpretations diverged at that point. It was fascinating to me to observe and listen to these discussions. Without a clue as to what the words meant, the inflections and gestures did not tell me the specifics of the obviously differing interpretations made by these two masters of the bush, but I understood the basics of the discussion anyway, and I enjoyed the entertainment that came from the disagreement in the analysis and the anticipated enjoyment that each one of them was planning on since the other was ultimately and undoubtedly very soon to be proven wrong.

Speaking quietly, we discussed the situation.

“What does he say?” I asked Richard.

“More important is what I think,” he responded.

“This bull lives completely alone, and is probably very old and very clever. Look at the size of his prints, - how deep they are. Of course, his horns could be anything, but there is no doubt he is an old loner.”

“So what’s the disagreement?” I asked.

“Joseph thinks we should look for a small group of them rather than one like this.

Easier to track, and better chances of finding a good trophy. He thinks we are wasting time on a singe old bull. Too many of us to be able to move quietly. With a group of three or four bulls, you can cover some of your approach because of the sounds they make. But an old bull, completely alone, - any sound he hears gets his attention.”

“But we’re going after this one anyway?” I asked.

“Mmm” he grunted, taking a look around. “I don’t think he will be far, but you can see how thick it is through here. We will have to move slowly and try and be quiet.”

“Lots of exposed rock” I said, “Easier to move quietly”

“But harder to track.”

“That’s your job.” I said smiling.

“Mine and Josephs” Richard smiled back. “But I’ll let him take the lead on this one since I overrode his opinion. We don’t want him feeling unappreciated.”

“Besides,” he said. “The real argument is if he is still close by or far away.”

“What’s your guess?” I asked.

“I’ll let you know when we find him,” said Richard.

This was obviously a difference of professional opinion that carried considerable bearing between the two of them.

Joseph was the lead tracker, with Silas as the number two man. Richard had said that Silas was nowhere near Joseph when it came to tracking, but Silas was friendlier, and more pleasant to hunt with. Joseph had a habit of never looking directly at you, and even when speaking to Richard he seemed to always be looking away. Joseph was also the main driver, a mistake in planning by Richard, because by committing him to the driving duties, he was obligated away from the primary role of tracker, which then fell to Silas. This disconnect would become evident in a few days, though not to anyone’s disappointment other than possibly to Joseph.

Shadrick, the game scout, had a large round face, with yellow eyes and a wide smile. He wore faded green military fatigues, had a pleasant demeanor, and he never hesitated to assist with tracking or any other effort, but with his washed-out uniform and his rattle-trap variant of a Kalashnikov, he looked more like a revolutionary than a game scout, and I thought that he could probably slip easily into either role as the situation demanded. Freedom Fighter or Game Scout, we liked him very much.

Observing the pathway where the tracks led away from the water, acknowledging my amateur status in a group of experts, I nevertheless privately estimated that it would take one or two hours to catch up to the bull. Anticipating the stalk in front of us, we all sat down in the soft sand and drank some water mixed with re-hydrating salts since the morning was already giving way to the heat of the day.

“You have solids, correct?” Richard asked me quietly.

“Two solids loaded, eight more in my belt, two soft nose in the extra pouch.”

“Only solids in this thick stuff” Richard added.

“Right,” I agreed.

I had ten flat-nosed 500 grain solids for the .470, two in the rifle and eight in my culling belt, plus two softs in a separate shell holder on the right side of my belt, for a total of twelve rounds, which seemed to me at least ten too many. My knife was on my belt in the small of my back, and my binoculars were in front of me bouncing in the straps around my shoulders. In my pockets were an energy bar and some jerky. Richard carried his Blazer .416 and a wallet with about eight rounds. Shadrick always had a magazine in his AK, which I assumed was loaded, but I never saw any brass. Joseph and Silas usually carried the water in a single backpack, and either Silas of Dustin carried my .505 Gibbs as a backup rifle, just in case.

We sat for maybe 10 minutes, and then, without speaking, we all began to move, standing up, we picked up our gear, double-checked rifles, and with no announcement that we were all ready but an understanding that such was the case, we set off on our planned pursuit in a serious and concentrated state, thinking about the heat, and the loads we were carrying, and the hours on the trail that lay in front of us, and we had not taken five steps when the brush in front of us exploded with the sounds of something very large moving at speed, fortunately in a direction away from us. With our rifles immediately on our shoulders we got a good look at him from the side as he broke out of a large tangle of combretum, not 20 yards in front of us, moving right to left, quartering slightly away. His horns were slate grey, and his body was dusty black with patches where no hair remained. Dried mud on the shoulders and boss made him look like a colonial barrister with a powdered wig. From the side his boss appeared large but we could not tell how wide he was, and from that close any bull looks big. There was not really time to shoot even if we had wanted to do so. We stood for a minute, eyes moving from the trail in front of us to each other in disbelief and then looking in the direction the bull had disappeared into, and we remained quiet, but Joseph dismissed our concern with a wave of his hand, having caught another glimpse of the bull at a distance through the trees, and moving away at a run, this observation only confirming that which he already knew. After so many days and miles of tracking, we had stumbled, completely by accident, into a sleeping bull.

We stood there for a few moments, all amazed by what had just happened.

“Well” I said to break the ice, “he was close by”

Joseph and Richard looked at each other, and with no words needed, the expressions on their faces spoke volumes that even I could understand.

We sat down again, and gave him about 10 minutes before we set off after him, and Joseph once again showing incredible skill followed him as easily as a train follows it’s tracks, but the wind, when not swirling, was once again at our backs. I was enjoying myself, taking in the sights and sounds, seeing the grasses and the trees and the blue sky. Marveling at the tracking, but trying to remain as vigilant as possible, hoping desperately to be the one that would pick him up when we got close, though I knew the chances of this were slim, we tracked through scrub and grassy open areas, and across rocky sections, places where the boulders lay strewn about, more ideal Leopard habitat, picking up the track once we got back to sandy soil. In one area there were large piles of a white powdery substance on the ground. In a whisper Richard explained that it was Hyena droppings, the coloration coming from the bones that they eat. We were moving along the trail, which had again taken us up over rocks and through grassy fields and thick mopane scrub and back into a rocky area when I stopped short as I suddenly realized that I smelled a strong odor of cattle. Looking up, I saw that Joseph had smelled it as well, and all of us having now stopped, realizing what we were smelling we turned to the left in unison and we immediately heard him crashing through the scrub once again at speed. Shadrick, who was behind me, got a good look and said that he was big, but we knew that after being bumped twice in such a short span of time he would keep running, and so we gave it up. With the sunlight and the thick cover interspersed with sunlit open areas, we were playing, and losing, on his home turf.

We were now well behind schedule, and as we headed to our meeting point, guided by the ever-present GPS, we knew that we were about 2 hours late for our bush lunch, where Dustin the apprentice PH would be waiting with Belinda and Alicia. Moving quickly and with no concern for stealth, it was during this time that I suggested to Richard that we take the afternoon off, to rest and perhaps re-focus, and hopefully stave off an ever-looming sense of frustration. The bulls were obviously there, but they were like ghosts, large grey-black ghosts that would let us approach to within a stone’s throw and then disappear at will. After 5 solid days of hunting we had only managed to glimpse one for a few seconds, and that purely by accident. Richard later told me that he was at first mortified at my suggested diversion, but by the time we arrived at our meeting place, he had changed his mind.

“Perhaps a chance to rest and refocus will change our luck.” He said.

Alicia and Belinda were sitting at the table having tea, having wisely chosen to not wait for us to eat. I unloaded my rifle, leaning it against a tree, and hung my culling belt with my solids and my knife over the end of the barrels. Removing my binoculars from around my neck I sat down and took off my boots.

“No luck?’ asked Alicia.

“Only bad.” said Richard.

“Have some lunch.” Said Belinda. “You’ll certainly feel much better after you eat.”

I sucked down an ice-cold Zambezi, and we dined on cold Boerwurs with noodles, salad with carrots, and a Kudu meat pie, finishing it all with another ice-cold Zambezi beer. During lunch, we told them what had happened, and our suggested plan for the evening. Belinda had been right about lunch, and everyone was agreeable to the plan for the evening, and so we went back to camp. My frustration, and my inclination to keep hunting, was no match for my fatigue, and back at camp we took a nap in the afternoon, the cool breeze off the lake blowing through the mosquito bar, and when we awoke we headed down to the lake at about half past four.

That evening, Castle Lager in hand, the Zambezi stocks dangerously low, we fished for Tiger fish off of the sandy beach, which was perhaps a quarter of a mile from camp. Somehow we had managed to leave what remained of the Zambezi behind, perhaps as a conservation effort. No matter, with bare feet in the cool sand, happiness comes easily. Accompanying the beer was some unbelievably delicious fried bream, caught and (presumably unknowingly) donated to our cause by writer and PH Lou Hallimore, and prepared right there on the beach by Mkusana and the replacement chef, both of them ever at the ready.

As the sun went down over the Zambian side of the lake, the light began to soften and cast a golden hue over the setting. In contrast high above was the indigo of the night sky with Southern Cross and other stars already visible, the deep blues lightening as your line of sight lowered to the blazing orange of the horizon. Animated conversations with commentary on the relative frequency with which one can expect to encounter buffalo, fishing prowess, and preferences regarding beer were followed by periods of silence and quiet reflection. There was a large houseboat across the lake, tied up on the Zambian side, and we could just hear the sounds of the people across the water, and further down we could see a herd of elephants coming down to drink. It felt good to cool our feet in the lake water, having no fear of crocs, as if such an idyllic place would not allow for any danger. We never caught any fish, though Alicia did have one strike, but the fire and the setting sun and the companionship, and the Southern Cross overhead were a far better take.

Part III

Dangerous Game

The next day, day six, rested and recharged, we started out again. We were only halfway through our Safari, but our record of one leopard-killed calf and one lone bull spotted, quite by accident, did not make me feel that the odds were in our favor. In spite of this pressure, or perhaps because of it, we decided to change our tactic, adopting a very relaxed attitude, almost as if it was day one. Again, Alicia and Belinda stayed behind in camp, and with Joseph, Silas, and Shadrick, we drove around a bit, to a few springs where we checked for tracks with no great exertion, and finding none we drove some more. I was still quite tired after going so hard for so many days, and I was content to sit for half a day, riding in the truck. The only game we saw was a pair of Francolin with their young chicks next to the road. They were so perfectly camouflaged that from five feet away you could not see them unless they moved.

Richard then drove us to a spot where the water came out of the ground in springs in a large open area. There were many small pools of water but no large ones, and the water apparently seeped back into the ground as it moved down a very slight incline. The remains of an elephant that had been killed only a month before were there, comprised of nothing more than one femur and the pelvis, both well chewed upon by anything and everything about. The soft ground would have allowed for deep impressions from anything that passed. But other than the fresh water, which was in no short supply, it seemed an unlikely spot and so I was not surprised when we did not find any fresh tracks.

Moving slightly uphill, and upwind, into the shade of the trees, Richard stopped at a clean shady area.

“If nothing else”, said Richard, “It’s a good spot for some tea and maybe lunch.”

“That’s fine with me,” I said, continuing in my relaxed operating mode.

Hunting all day, every day, except for our evening fishing the day before, up hill and down, in the African sun, burning any excess calories I managed to consume, and carrying rifle, knife, binoculars, ten solids in the culling belt, plus two softs in the separate pouch, with the odd energy bar in my pocket, it seemed I was always hungry. “Good way to live” I thought to myself. “Eat all you want, burn off all the excess. The biggest worry is how long the Zambezi beer will last.”

“Castle is generally preferred.” Richard stated to me again one day as I was lamenting the shortage.

“I can drink castle,” I said. “But it’s too bitter for me to really like it.”

“Besides, if we are on the Zambezi then we should drink Zambezi. Remember?”

“Yes I remember. We are on Lake Kariba, to be precise.”

“Yes but the Lake wouldn’t be here if not for the river.”

“River, Lake, drink your beer.”

Upwind of the kill sight we found a park-like area, with short yellow grass surrounded by Mopane trees, in a sort of natural African Stonehenge-like arrangement, the smaller trees in circular form paying homage to a large Baobab. There was minimal shade from the Baobob as it had no leaves on it, July being winter south of the equator, but the trunk was so large that it cast a good amount of shade, and I remembered Wally at the Sijarira camp had said something happens to you if you rest in shade of a Baobob tree, though I did not remember what it was. From the back of the Land Rover came the small folding lunch table, and Richard and I removed our boots and socks, and relaxed most contentedly, enjoying our lunch, and discussing the benefits of living a good life. Richard tried to teach me some Ndebele words, mostly dealing with “here” as opposed to “there” and so on, and then he went back to the truck and returned with two bug huts, screened tent-like enclosures to rest in while keeping insects at bay. I later made a mental note to add the bug-hut under the shade of a Baobab to the list of places where I sleep best.

Bush lunch is one of my favorite things in Africa. The finest cuisine on china and linen in the best restaurants in the world cannot compare with Boerwurst and cold pasta, kudu-meat filled pastry, cold salad with carrots, ice cold Coke or Zambezi beer, (if the PH was considerate enough to bring any) and some chocolate for desert, in the shade of a baobab, on the shores of Lake Kariba, in the Zambezi Valley of north-western Zimbabwe. Then a nap in a bug hut, enjoying the cool breeze, taking in the sounds, sights, and smells of the place where I am supposed to be, I couldn’t be more content. Then I remembered that Wally had said that resting in the shade of the Baobab makes you crazy. Well maybe so, but satisfied from lunch, happy to be in Africa, excited to be hunting buffalo, and watching the frustration of the mopane flies as they swarmed around me but were held at bay by the bug hut, I was prepared to risk it.

Unceremoniously, we awoke about an hour later, wanting to get going but not wanting to get up. We sat up, put on our boots, and slowly, we finally began moving. Joseph and Silas had apparently scouted about while we rested, and some 100 yards from our position they had found some relatively fresh spoor. Richard spoke with the two of them briefly, and based on an assumption from the general direction of the tracks, the plan was for Joseph to take the Land Rover to a point in the road about 5 miles away, marked by a tremendous Baobab with a large cavity in the trunk, and wait for us there. If anything changed we would call him on the radio. While he drove he would also scan the road, as always, for sign, possibly picking up some likely looking spoor en route. Starting out, rested and content, rifle over my shoulder African style, we headed away from the clearing into some heavier cover. Soon we were on the tracks, and we found ourselves moving through a dark forest-like area where the growth made a canopy overhead, with lots of tangle and vines underfoot, and the ground had no cover but the dirt, which was moist, and scattered with soft leaf litter, so that when you saw a track, it was in a spot where there were no leaves, and the moist dirt that was kicked up showed darker than that surrounding it, or the dirt was thrown onto the leaves. Some of the tracks were hard to find, but when you saw one it was very clear.

Spread out in a line, with Richard on the left, Silas in the middle followed by Shadrick, and me on the right, we stopped for a moment. Silas, looking at Richard, held up two fingers, Richard held up one, and then they looked at me. I held up one as well. There were four of them. Communicating without speaking, the soft low whistle used to gain attention, the sound low and dropping in pitch, like some mysterious African bird that is often heard but never seen, with eye movements and gestures to indicate direction, hand signals and movements unexaggerated, and we continued very stealthily, but as the canopy started to open up, the sunlight that penetrated meant that the ground was now not as moist, and the dry leaves were making more noise. The tracks then made a sharp turn to the left, and leaving the dark forest area, we stopped where a large tree was down, and going around it brought us close together for conversation in whispers.

“Four bulls” said Richard, “This is exactly what we have been looking for”

“Tracks are fresh?” I inquired, hoping as much as verifying. I thought that they were, but I was still the rookie in the party.

“They look good, but hard to tell, in this type of area, with no sunlight or wind, they can look fresh for a long time.”

“Here’s our plan.” He continued, “We are going to stay after these four. It may take a day or even two, but sooner or later we’ll catch up to them.”

“I like it” I said. “But what about Joseph?”

“He’s gone in quite the wrong direction, but no matter, we’ll radio him later.” This will be Silas’ chance to shine.”

I could feel my anticipation building up inside of me. I was excited about the prospects on the ground in front of us, and Richard continued;

“We’re moving well enough, but if these tracks are from today like I think they are, by now they have probably stopped, and we could find them in two or three miles, but you never know. We might also come up on them at any time. Stay alert and watch where you step.”

I nodded in agreement, and we started again, and now, after about a quarter of a mile, moving out of the canopied area, on a high open plateau, I could just see the sparkle of the sunlight reflecting on the lake in the distance. Moving down the hill, we were coming onto a draw, and the first steps over the rim where the ground fell away were very steep. It was warm in the sun, and the dry Mopane leaves on the ground made a lot of noise. I was again thinking that while tracking an animal that weighs almost a ton is fairly easy, to spot and then approach them would be the difficult part. We would have to get lucky and spot them at a distance, and with the noise we were making, I now found myself hoping that they were further away than closer. The noise was really unbelievable. Silas was now in front, and with the rocks and the short grass of the hillside the tracking was much harder, so that I dropped back into following mode. Richard was in front with Silas, then me, and Shadrick following behind. The noise continued to bother me, and my awareness of it seemed to heighten my frustration of the days, and the less than ideal circumstances of our present situation, and in the sun, making noise, sweating now, and half-slipping down this hillside, we all froze in quick succession, as Silas had them.

STORY CONTINUES BELOW.

COMMENT HERE: http://forums.nitroexpress.com/showflat.php?Cat=0&Number=197512&an=0&page=0&vc=1