NitroX

|

| (.700 member) |

| 10/02/20 10:00 PM |

|

|

|

A driven game hunt with a difference

NOWHERE along the foothills of the Himalayas is there a more beautiful setting for a camp than under the Flame of the Forest trees at Bindukhera, when they are in full bloom. If you can picture white tents under a canopy of orange-coloured bloom; a multitude of brilliantly plumaged red and gold minivets, golden orioles, rose-headed parakeets, golden-backed woodpeckers, and wire-crested drongos flitting from tree to tree and shaking down the bloom until the ground round the tents resembled a rich orange-coloured carpet; densely wooded foothills in the background topped by ridge upon rising ridge of the Himalayas, and they in turn topped by the eternal snows, then, and only then, will you have some idea of our camp at Bindukhera one February morning in the year 1929.

Bindukhera, which is only a name for the camping ground, is on the western edge of a wide expanse of grassland some twelve miles long and ten miles wide. When Sir Henry Ramsay was king of Kumaon the plain was under intensive cultivation, but at the time of my story there were only three small villages, each with a few acres of cultivation dotted along the banks of the sluggish stream that meanders down the length of the plain. The grass on the plain had been burnt a few weeks before our arrival, leaving islands of varying sizes where the ground was damp and the grass too green to burn. It was on these islands that we hoped to find the game that had brought us to Bindukhera for a week's shooting. I had shot over this ground for ten years and knew every foot of it, so the running of the shoot was left to me.

Shooting from the back of a well-trained elephant on the grasslands of the Tarai is one of the most pleasant forms of sport I know of. No matter how long the day may be, every moment of it is packed with excitement and interest, for in addition to the variety of game to be shot-on a good day I have seen eighteen varieties brought to bag ranging from quail and snipe to leopard and swamp deer-there is a great wealth of bird life not ordinarily seen when walking through grass on foot.

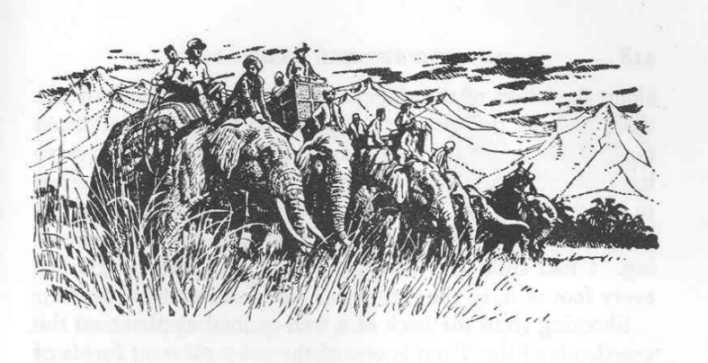

There were nine guns and five spectators in camp on the first day of our shoot that February morning, and after an early breakfast we mounted our elephants and formed a line, with a pad elephant between each two guns. Taking my position in the centre of the line, with four guns and four pad elephants on either side of me, we set off due south with the flanking gun on the right-fifty yards in advance of the line - to cut off birds that rose out of range of the other guns and were making for the forest on the right. If you are ever given choice of position in a line of elephants on a mixed-game shoot select a flank, but only if you are good with both gun and rifle. Game put up by a line of elephants invariably try to break out at a flank, and one of the most difficult objects to hit is a bird or an animal that has been missed by others.

When the air is crisp and laden with all the sweet scents that are to be smelt in an Indian jungle in the early morning, it goes to the head like champagne, and has the same effect on birds, with the result that both guns and birds tend to be too quick off the mark. A too eager gun and a wild bird do not produce a heavy bag, and the first few minutes of all glorious days are usually as unproductive as the last few minutes when muscles are tired and eyes strained. Birds were plentiful that morning, and, after the guns had settled down, shooting improved and in our first beat along the edge of the forest we picked up five peafowl, three red jungle fowl, ten black partridge, four grey partridge, two bush quail, and three hare. A good sambhar had been put up but he gained the shelter of the forest before rifles could be got to bear on him.

Where a tongue of forest extended out on to the plain for a few hundred yards, I halted the line. This forest was famous for the number of peafowl and jungle fowl that were always to be found in it, but as the ground was cut up by a number of deep nullahs that made it difficult to maintain a straight line, I decided not to take the elephants through it, for one of the guns was inexperienced and was shooting from the back of an elephant that morning for the first time. It was in this forest-when Wyndham and 1 some years previously were looking for a tiger-that I saw for the first time a cardinal bat. These beautiful bats, which look like gorgeous butterflies as they flit from cover to cover, are, as far as I know, only to be found in heavy elephant grass.

After halting the line I made the elephants turn their heads to the east and move off in single file. When the last elephant had cleared the ground over which we had just beaten, I again halted them and made them turn their heads to dle north. We were now facing the Himalayas, and hanging in the sky directly in front of us was a brilliantly lit white cloud that looked solid enough for angels to dance on.

The length of a line of seventeen elephants depends on the ground that is being beaten. Where the grass was heavy I shortened the line to a hundred yards, and where it was light I extended it to twice that length. We had beaten up to/the north for a mile or so, collecting thirty more birds and a leopard, when a ground owl got up in front of the line. Several guns were raised and lowered when it was realized what the bird. was. These ground owls, which live in abandoned pangolin and porcupine burrows, are about twice the size of a partridge, look white on the wing, and have longer legs than the ordinary run of owls. When flushed by a line of elephants they fly low for fifty to a hundred yards before alighting. This I believe they do to allow the line to clear their burrows, for when flushed a second time they invariably fly over the line and back to the spot from where they originally rose. The owl we flushed that morning, however, did not behave as these birds usually do, for after flying fifty to sixty yards in a straight line it suddenly started to gain height by going round and round in short circles. The reason for this was apparent a moment later when a peregrine falcon, flying at great speed, came out of the forest on the left. Unable to regain the shelter of its burrow the owl was now making a desperate effort to keep above the falcon. With rapid wing beats he was spiralling upwards, while the falcon on widespread wings was circling up and up to get above his quarry. All eyes, including tllose of the mahouts, were now on the exciting flight, so I halted the line.

It is difficult to judge heights when there is nothing to make a comparison with. At a rough guess the two birds had reached a height of a thousand feet, when the owl-still moving in circles-started to edge away towards the big white cloud, and one could imagine the angels suspending their dance and urging it to make one last effort to reach the shelter of their cloud. The falcon was not slow to see the object of this manoeuvre, and he too was now beating the air with his wings and spiralling up in ever-shortening circles. Wouuld the owl make it or would he now, as the falcon approached nearer to him, lose his nerve and plummet down in a vain effort to reach mother earth and the sanctuary of his burrow? Field glasses were now out for those who needed them, and up and down the line excited exclamations - in two languages - were running.

'Oh! he can't make it.'

'Yes he can, he can.'

'Only a little way to go now.'

'But look, look, the falcon is gaining on him.' And then, suddenly, only one bird was to be seen against the cloud. Well done! well done! Shahbash! shahbash! The owl had made it, and while hats were being waved and hands were being clapped, the.falcon in a long graceful glide came back to the setnul tree from which he had started.

The reactions of human beings to any particular event are unpredictable. Fifty-four birds and four animals had been shot that morning - and many more missed - without a qualm or the batting of an eyelid. And now, guns, spectators, and mahouts were unreservedly rejoicing that a ground owl had escaped the talons of a peregrine falcon.

At the northern end of the plain I again turned the line of elephants south, and beat down along the right bank of the stream that provided irrigation water for the three villages. Here on the damp ground the grass was unburnt and heavy, and rifles were got ready, for there were many hog deer and swamp deer in this area, and there was also a possibility of putting up another leopard.

We had gone along the bank of the stream for about a mile, picking up five more peafowl, four cock florican - hens were barred - three snipe, and a hog deer with very good horns when the accidental (please turn your eyes away, Recording Angel) discharge of a heavy high-velocity rifle in the hands of a spectator sitting behind me in my howdah, scorched the inner lining of my left ear and burst the eardrum. For me the rest of that February day ,vas torture. After a sleepless night I excused myself on the plea that I had urgent work to attend to (again, please, Recording Angel) and at dawn, while the camp was asleep, I set out on a twenty-five-mile walk to my home at Kaladhungi.

The doctor at Kaladhungi, a keen young man who had recently completed his medical training, confirmed my fears that my eardrum had been destroyed. A month later we moved up to our summer home at Naini Tal, and at the Ramsay Hospital I received further confirmation of this diagnosis from Colonel Barber, Civil Surgeon of Naini Tal. Days passed, and it became apparent that abscesses were forming in my head. My condition was distressing my two sisters as much as it was distressing me, and as the hospital was unable to do anything to relieve me I decided - much against the wishes of my sisters and the advice of Colonel Barber - to go away.

I have mentioned this 'accident' not with the object of enlisting sympathy but because it has a very important bearing on the story of the Talla Des man-eater which I shall now relate.

Extracted from Jim Corbett's "The Temple Tiger"

Tags:

Howdah. Corbett, Elephant Drive, India, Double Rifle, Tiger

http://forums.nitroexpress.com/showflat.php?Cat=0&Number=2973&an=&page=0&vc=1