NitroX

|

| (.700 member) |

| 04/03/17 09:56 PM |

|

|

|

http://www.thefield.co.uk/shooting/holland-holland-38434

***

Holland & Holland: The Royal, simply the best

The Field January 1, 2017

As well as being a thing of great beauty Holland & Holland’s impressive sidelock has been an inspiration to gunmakers worldwide, says Sam Rickitt of Venaticus Ltd

The Royal's detachable lock system.

No sidelock has been more widely copied than than Holland & Holland Royal over the past hundred years. Douglas Tate celebrates the impressive sidelock that has inspired gunmakers worldwide.

For more on the Holland & Holland Royal, read Michael Yardley’s review, the Holland and Holland Royal gun review.

HOLLAND & HOLLAND

If imitation truly is the sincerest form of flattery, no gunmaker in the world should be more flattered than Holland & Holland, because no sidelock has been more widely copied over the past hundred years than the Holland & Holland Royal.” So said Michael McIntosh and David Trevallion in their slim volume Shotgun Technicana. “In terms of imitation, it’s fair to say that the Holland action is the most famous ever invented,” they continued.

The Royal’s detachable lock system.

Surf firearm sites or leaf through gunmakers’ catalogues and you’ll find guns described as: “apatura automática estilo H H” (Grulla); “sistema Holland & Holland” (Piotti); “con batterie tipo H&H” (Bernardelli); “H&H assisted opening mechanism” (Arrieta); or “locks are made in house to the proven H&H design” (AA Brown); or “Apertura automática estilo H H (Armas Garbi). Most fine sidelocks emulate the H&H action rather than Purdey. Why? One answer may be simplicity.

Where competitors offer complexity, the locks, ejectors and self-opening system of the Holland & Holland Royal are simple. The Royal may be the most recognised gun action in a city with more fine gun actions than any other in the world, yet it is one of the few not based on a patentable propriety action; rather, it evolved in incremental steps often involving the simplification of previously complex mechanics. The final result is an action stripped to its essence, its structure and function the primary priority.

FIRST MUZZLE-LOADERS

Holland & Holland began with Harris Holland, who initially offered muzzle-loaders but breech-loaders naturally followed. Both were high quality and appear to have been built in the trade and merely engraved “H Holland” or “HJ Holland”. Holland was unique among London’s pre-eminent gunmakers; he was not part of the family of metaphoric Manton descendants. Unlike his immediate competitors – Purdey, Boss, Grant and Lancaster – he claimed no lineage to the King of the Gunmakers. He was a tobacconist with a background in barrel-organ building and musical-instrument retailing who pulled out all the stops when he began offering guns. But he wouldn’t hit his high note until his nephew piped up.

Arts & Crafts-inspired engraving.

If you were you thumbing through these pages in the winter of 1876 you might have spotted this:

Alteration of name:

Mr H Holland begs to inform his friends and customers that having taken his nephew, Mr Henry Holland, into partnership, in future the business will be carried on by and

under the joint names of HOLLAND and HOLLAND, 98, New Bond-street, London.

The appended moniker signified that the older Holland had taken his brother’s son into business during 1860 with a view to having him train as a hands-on, practical gunmaker and was now making him a partner. Both knew that successful breech-loading designs could establish reputations and create fame and fortune. The nephew fathered 47 firearms-related patents but it may have been his ability to spot simplicity in the design of others that shot Holland & Holland to prominence.

The crowning achievement of their partnership was, and still is, the Royal side-by -side sidelock. In its initial incarnation the Royal was a Heath Robinson contrivance in which one lock cocked on opening and the other upon closing. But asymmetrical designs tend to be weaker on one side or the other and it was soon discovered that the left lock was liable to get out of whack. The problem was resolved by the simple expedient of duplicating the right hand lock. Donald Dallas, writing in Holland & Holland: The Royal Gunmaker, says it was introduced “in the spring of 1885 and has continued in production ever since as the flagship of Holland & Holland”. The trademark “The Royal” was granted that same year.

EXCEEDINGLY SIMPLE

Describing the modified, symmetrical Royal in 1892, Lord Walsingham and Sir Ralph Payne-Gallwey noted: “We consider the mechanism exceedingly simple and effective, and very secure from the chance of rusting from wet or fouling. The action is hard to beat for qualities of simplicity, strength and, above all, safety. We are very satisfied with this ‘Royal ejector’ of Messrs Holland, and up to date we do not think a shooter could purchase a better or safer weapon.” They summarised the chief advantages of the Royal thus: “The simplicity and strength of the action and non-liability of the locks to get out of order. Regularity and delicacy of the pulls of the triggers. The ease with which the gun can be opened. Absolute safety of the lock mechanisms,” concluding that: “In the ‘Royals’ not only are the triggers automatically locked but in addition there is an intercepting safety block on each lock, always in position in front of the hammers, whether the top slide is at safe or not, so that no jar or blow can fire the gun unless the triggers are purposely pulled.”

Later, Holland & Holland would adopt a rocking cocking lever, patented by two men both called John Rogers, presumably father and son, that further simplified the Royal. The mechanism has not materially changed since.

Teddy Roosevelt, an Holland & Holland client.

Here is how Jan Roosenburg and Michael McIntosh describe it in their book, The Best of Holland & Holland: England’s Premier Gunmaker, “In subsequent revisions carried out over the next few years, the two-lever cocking system was replaced with a simpler arrangement in which a single lever extends through each side of the action bar into the lock cavity of the frame. This is the now classic Holland & Holland system, copied worldwide. It’s wonderfully simple, as efficient and durable as any cocking system ever devised.”

It’s worth pausing here to note that the simplicity, strength and safety of the Royal was not lost on African dangerous game hunters, where the price of getting things wrong can be steep. In its double rifle incarnation the Royal would become immensely popular. When Theodore Roosevelt took one on safari in 1909, he said of it: “I do not think there exists a better weapon for heavy game.”

This pattern of spotting simplicity in the inventions of others would repeat itself with another aspect of Royal design, the Holland & Holland two-piece ejector. Dallas has said it “is world famous and has been widely copied since its introduction in the early 1890s”. At that time, driven-shooting led to the use of ejectors to kick free spent cartridges, allowing faster reloading. Many were tried but most were found wanting. Early ejectors were chain-reaction devices with multiple parts just waiting to go wrong. But by the 1890s, the fine gun trade was beginning to settle on designs based on the over centre tumbler concept, identical in principle to the mechanism that springs a pen knife shut. Collectively known as the Southgate system for Thomas Southgate, an outworker to the gun trade, they were more likely the brainchild of one Thomas Perkes.

The Royal’s simplicity of action has inspired it to be copied by many.

Despite patenting several ejectors, Henry W Holland adopted a design by the gunmaker colloquially know as the “Inventor to the London Trade”, Frederick Beesley. Holland’s ejectors were clearly attempts at simplification and contemporary advertisements appear to claim him as the inventor of the two-piece ejector but Major Burrard makes nonsense of this. “The real credit for the invention, however, should be given to the late Mr F Beesley, who was one of the most fertile inventors the gun trade has known as it was Beesley who sold his idea to Messrs Holland & Holland.” Curiously, in Beesley’s patent drawings the dipped edge lockplates of an early Holland & Holland Royal can clearly be seen along with a Rogers-style cocking lever.

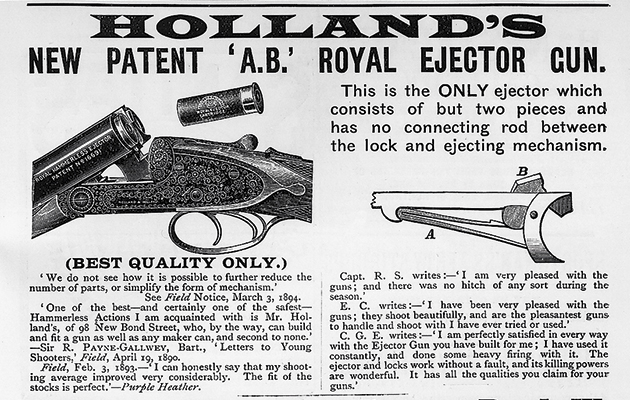

Christened the “AB” for its two parts, it garnered great reviews. “Mr Holland has abolished the lock in the fore-end altogether. Instead of a lock of eight or more parts, he omits all the parts but two – A and B… that is to say a mainspring and a kicker,” said the sporting magazine Land and Water. “This is beautifully simple and effective, and we are confident will attract much attention from shooting men.” During 1894, the magazine added: “We do not see how it is possible to further reduce the number of parts or simplify the form of the mechanism.”

“The end result of the updated Royal was a very handsome, efficient gun that would remain essentially the same to this day,” writes Dallas, adding, “Only with the advent of the self-opening mechanism in 1922 would major changes be made.”

SELF-OPENING SYSTEM

Though Henry W Holland was joint patentee for the company’s self-opener of 1922, it was likely his factory manager, William Mansfield, who invented it. Intended to challenge the supremacy of the Beesley Purdey design that, in the early 1920s, had 40 years of success behind it and was the standard of comparison within the London gun trade, the Holland and Mansfield opened to great reviews. The Field of 22 March 1923 called it “decidedly simple and ingenious… There is nothing to get out of order, and nothing which is in the least likely to go wrong… it is the easiest closing… self-opening ejector which we have yet tried. We accordingly welcome Holland’s latest invention as a decided advantage on the refinement of the science of gun building.” Major Burrard wrote: “This mechanism gives the easiest closing for a self-opening ejector that I have ever known.” Both references obviously dig at the Beesley Purdey.

An acanthus motif made The Royal more feminine.

The Holland and Mansfield self-opener is based on a coil spring operating in the recess below the barrels. The spring is compressed when the action is closed. When the bolts are withdrawn by the turning of the top lever this spring expands pushing a slide against the knuckle of the action easing the gun open. The facility with which the gun then closes is, according to Burrard, partly “because the leverage exerted against the end of the slide is very great, and partly because the whole of the force exerted by this lever is applied directly on to the end to the slide”. Like everything else to do with the Holland & Holland Royal it was widely copied for its simplicity and ease of maintenance but also because it operates separately from other elements of Royal design and is consequently more adaptable. One competitor who offers the Holland and Mansfield self-opener has this to say: “Coil-spring operated the strength can be adjusted by changing the spring, to give mildly assisted, easy or self opening. This system is independent of all other functions. The slide can be omitted during manufacture to produce a standard opener.”

HAND-DETACHABLE LOCKS

At the turn of the 20th century the British fine gun trade experienced a groundswell of interest in hand-detachable locks. Both Westley Richards and Joseph Lang provided multiple variations on the theme but none were more elegantly simple than Henry W Holland’s patent of 1908. By attaching an external thumb lever to the head of the side nail H&H created, initially at least, an instantly recognisable signature feature. It was the final addition to the planet’s most recognisable fine gun. It endures to this day and is widely copied, especially in Spain. Holland & Holland has built, and continues to build, guns on many designs but it is the simplicity, strength and safety of the Royal mechanism that has vaulted the company to global renown. However, no discussion of its merits would be complete without a look at the physical beauty of the gun, the allure of appearance that extends beyond mechanics.

Some of the parts that make up The Royal’s locks and cocking mechanism.

When the Royal first appeared the action was represented by engravings in sporting periodicals such as this one in 1885 and Land and Water in 1893. It was a time when the

aesthetics of the hammer gun were morphing into hammerless designs. Despite transcending competitors’ designs for appearance, the Royal was at first unlovely. Engravings show a protruding third fastener, frog-eye cocking indicators, a swamped rib, a clumsy square back Birmingham-style action and leg o’mutton lock plates. Over the years, incremental refinements produced an altogether more elegant design; the horns of the stock were extended to kiss the beaded flattened ball fences and the action filled with a double bar while the dipped edge lock plates were dispensed with to be replaced by an uninterrupted sweeping curve. The result was at once modern and gorgeous.

Only one element remained, the engraving. At the time, London’s fine gun trade was dominated by conservative bouquet and scroll; Holland & Holland needed something different to set it apart. The company’s engravers found inspiration in the Arts & Crafts movement and the fertile mind of William Morris. Like their Pre-Raphaelite contemporaries, the Arts & Crafts folk rejected manufactured goods and design and promoted a revival of traditional, artisanal craftsmanship. Morris’s greatest achievement was, perhaps, the contiguous patterns he produced for textiles and wallpaper. The Royal came of age in an era of applied arts in which design was effectively the decoration of an object. By conflating mechanical simplicity with an acanthus motif evocative of William Morris’s wallpaper designs, Holland & Holland created a unique style – more feminine than masculine, it is the sexiest of guns.

Advertising the new patent “AB” Royal ejector gun.

Today we conflate “simple” with “facile” or even “easy to do” but when a fine gunmaker uses the term it can mean “takes a lifetime to learn”. Ingenuity and adaptability are perhaps the keys to Henry W Holland and his pared-down Royal. He was a man who willingly jettisoned his own inventions in the face of improvements from others but also recognised the value of aesthetics. Were he alive today, he could not fail to be impressed by the extent to which his efforts have contributed to the wealth of guns produced worldwide all these years later.

In his coffee-table tome, The Best of British: A Celebration of British Gunmaking, the American Vic Venters said the Royal “has long reigned as the world’s most copied sidelock. Relatively simple and ultra-reliable, it simply works, and is easier to build, regulate and stock than designs like the Beesley.”

“Good design,” said Dieter Rams, “is as little design as possible.” The industrial designer could have been describing the Holland & Holland Royal.

Author’s note: I am indebted to Donald Dallas, whose book, Holland & Holland “The Royal” Gunmaker, The Complete History provided much of the source material for this article. Copies are available from H&H at www.hollandandholland.com