| David_Hulme |

| (.275 member) |

| 04/04/07 06:42 AM |

|

|

[image]

[/image]

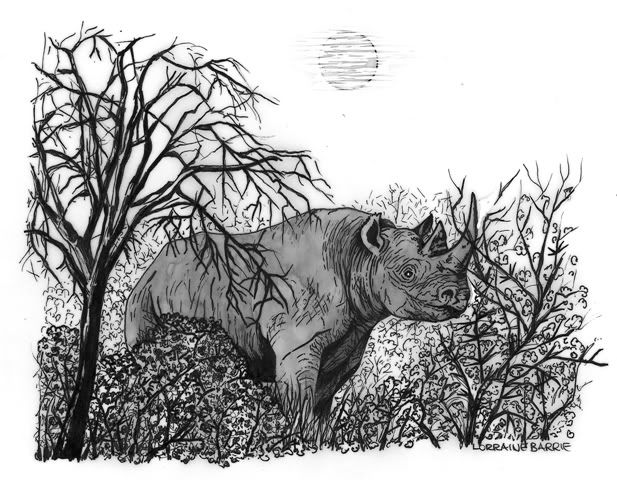

[/image] THE REFINED ART OF DE-HORNING A RHINOCEROS

I return to the Lowveld for that is where my soul truly is. It is a changed Lowveld that I return to, but I believe it to be changed for the better. The cattle/ wildlife transition is at an advanced stage and the bush is lusher than I have ever seen it. The grass cover specifically is phenomenal, most pleasing indeed. There are more wild animals than ever before on the ground and an increased diversity of species. Certain species have been reintroduced to the area and, for the first time in many years, Ruware has resident elephant, rhino, buffalo and wild dog roaming about. The elephant are an orphan herd* captured in Gonarezhou National Park and trucked to Ruware, as part of an elephantine translocation exercise never before achieved. This translocation operation was coordinated and carried out by a certain Mr Clem Coetzee, a living legend in Zimbabwean conservation circles. Yes, this Lowveld is certainly different to the Lowveld of the 80’s, and it is good.

* Orphaned as a result of culling, which is the shooting of entire herds. Culling is a distasteful but necessary elephant control measure. Before translocation came into being, there was no option but to cull – lebensraum and all you know.

During the 1990’s, the National Parks and Wildlife Department, in conjunction with the Veterinary Department, implemented a programme aimed at de-horning the country’s entire black rhinoceros population. Not that there was much of a population remaining at that stage. Most people will remember that, during the 80’s, Zimbabwe’s rhino suffered heavy losses at the hands of poachers. In reality, they were all but totally eliminated, the scale of the slaughter being nothing short of prodigious. A national herd census conducted in the early 80’s placed the black rhino population in excess of three thousand animals, these were reduced to a mere three hundred by 1990. Only a handful of heavily protected survivors weathered the storm and these were, for the most part, harboured in special sanctuaries and private reserves throughout the country. One such sanctuary was the Chiredzi River Conservancy.*

* The CRC was founded in 1989 by Buffalo Range, Ruware and Mungwezi Ranches. The basis of this foundation was a common desire to further wildlife populations in the area.

The incentive behind the wholesale eradication of the rhino was the extreme value placed on rhino horn by traders operating in the Far and Middle East. The intended objective, therefore, in de-horning the population’s remnants, was to remove the incentive. It was logically deduced that if the rhino were hornless they would be valueless and a cessation in poaching would ensue, for a while anyway, until the horns grew again. In principle it was a sound plan, however, in Africa (and particularly in African wildlife conservation), the best-laid strategies have the uncanny ability of totally falling apart at the seams. I do not wish to sound overly cynical here, and the de-horning exercise possibly did slow down the killing to an extent in certain areas, bearing in mind that by that time the rhino war was at an advanced stage, most of the damage long since done. Anyway, I am not qualified to judge whether or not the exercise was worth the effort or cost, although one thing I can say with absolute conviction is that the poaching continued. Various conservation areas continued to lose rhino to poachers, even after they had undergone de-horning. It was said that the poachers were killing these de-horned animals for the paltry reward of the horn stumps, which could not be removed during the procedure due to the delicate nerve endings they contain. I presume that there was more to it. I believe that the poachers continued to kill out of sheer malice. Resentment resulting from the very fact that the rhino had been de-horned at all, that they had been deprived of a major source of income generation. The post de-horning killings were actually revenge killings. In what could have been yet another one of Africa’s countless ironies, the de-horning programme may have ultimately done more harm than good. Nevertheless, whatever the consequences may have been, and whatever my own presumptuous opinion may still be, the exercise did take place and it was obviously a mammoth undertaking. I was fortunate enough to accompany the de-horning team on several operations when they arrived on Ruware in the south-east Lowveld. One of those affairs turned out to be a very interesting experience indeed. This is how events transpired on that day.

We assemble very early in the morning at Chehondo, our home. The team comprises a total of eight people including: Euan Anderson, a government appointed veterinarian and friend; Sally, a young trainee vet from America; Rob Style and Tore Balance, good neighbours and friends; Dad and I and a couple of Ruware trackers – Zondani and Chibobo. Although it is barely 5 am, the sun is already well up, the sky devoid of cloud. There is no early morning chill to speak of, and one can tell that the day shall pan out to be a typical lowveld midsummer’s day. Initially hot and, as time passes, progressively hotter. ‘Yes,’ I think – as we fortify ourselves with tea and receive the ‘prior to departure plan of action’ – ‘today our mettle shall be thoroughly put to the test.’ Nobody can truly appreciate what it feels like to traipse around the lowveld bush at noon in the middle of summer, unless one has personally experienced it. It is energy sapping to say the least. At times the heat is suffocating and even breathing becomes a struggle.

We know the approximate location of the day’s intended ‘target’, which is a bull christened Walter. This rhino is named after a wealthy German industrialist who is one of the rhino project’s more generous benefactors. Walter (the rhino) most often resides in an area known as number 4, between the Matema road and the Chiredzi River. Walter (the German) resides in Berlin, I think! After covering up with copious quantities of sun block, we set off at high speed in a small convoy of two Land Rovers in search of Walt. I am standing with the trackers in the back of the rearmost vehicle. By the time we reach the Matema road, I have been transformed into a brown man, with most of the dust cast up from the lead vehicle having adhered in a thick film to my sun-blocked face, arms and legs. Good camouflage anyway I reason, spitting sand from my mouth and grinding away pointlessly at my grit filled, sun block doused, weeping eyes.

After cruising slowly down the Matema road a short distance scanning for rhino spoor, we discover Walter’s tracks. They are fresh and heading in an east-west direction, down into the dense ravine of the Chiredzi River Valley. It is generally assumed - by everyone experienced enough or audacious enough – that Walter is lying up in the thick band of bush flanking the river. Because of this majority assumption, Euan proposes that only he and Zondani (the more experienced tracker) carry out the follow up, so as to approach with the minimum of disturbance. Euan says that once he has Walter darted and immobilized, he will contact us via hand-held radio and we should follow up as fast as possible, to assist with the physically demanding de-horning process. No one argues, Euan is the boss and a thorough professional to boot. I am secretly relieved. The option of lying comfortably under a shady tree certainly seems more attractive than the alternative – beating around the bush in the blistering heat with restricted visibility and the prospect of facing a cantankerous rhino at any time! Of course, I keep my cowardly thoughts to myself. With Zondani hot on the trail, and Euan, his dart gun and small skeleton kit of essential equipment close behind, the duo disappears from view. We settle down to wait. Initially I pass the time chattering aimlessly about nothing with my friend Rob, and for a short while the two of us attempt chatting up the American girl. She soon tires of our country bumpkin banter and particular brand of humour (if indeed we have one), obviously having seen and heard it all before.

Predictably, I soon become bored and irritable. I do not enjoy playing the waiting game, for I am not a patient person and it often seems to me that I have spent a great deal of my life waiting for something to happen. In Africa, patience is a very beneficial virtue, a necessity actually. It is a lesson that the Old Man constantly stresses the importance of, and one that I have yet to fully grasp. The land and the spirits are timeless the Old Man would say, they wait and so shall you. This wait becomes a particularly tedious one. As the hours drag by and we receive no word from Euan, the sun climbs ever higher into the heavens and the heat gradually dries up all efforts at conversation. Even the shade becomes irrelevant – such is the sun’s might on this day. As the sweat pours from overly active pores, and the heat intensifies dramatically, so do the efforts of the incessant mopani flies. Infuriating beyond belief, these tiny flies arrive in multitudes and never cease in their quest to obtain moisture from whatever source one makes available – eyes, ears, nose or mouth. Mopani flies have the ability to make a person decidedly uncomfortable and, on this day, they become unbearable. There is a theory that if you kill a mopani fly, more than ever before will come to irritate you, something to do with the scent exuded from a squashed fly attracting the masses. I am not a proponent of this theory, personally believing that they would arrive either way. Mopani flies are the most persistent irritants I have ever come across, in my opinion worse than both tsetse flies and mosquitoes.

The sun becomes fiercer and the mopani flies re-intensify their efforts. My cowardly nature is overwhelmed by the concerted combination of heat, fly and boredom, and I find myself contradicting my previous thoughts, now wishing that we had all tracked down Walter together. Although, God alone only knows what Euan and Zondani are going through at this particular time, melting one would assume. I silently wonder where they could be. Why are they taking so long to call? What is going on out there? Are they experiencing difficulty locating Walter? Surely not, he is usually a very territorial rhino, never straying far from number 4. And so we sit and wait – brushing away mopani flies, sweating profusely and gulping down mouthfuls of warm water. The sun reaches its merciless zenith and remains there for what feels like an eternity. Then, at a painstakingly slow pace, it moves across into the west.

The call, when it eventually comes, is a fuzzy, crackling, fading affair. The signal is very poor and we strain to make out what is being said. Transmissions are broken and scrambled with long periods of shshshshshshshsh, interspersed occasionally by short, inaudible bursts of Euan’s distorted voice. The lack of continuity makes it impossible to make any sense of. Finally, after a lengthy period of confusion, we hear him repeat the word ‘Mungwezi’ several times. Mungwezi is the neighbouring ranch belonging to Tore Balance. We presume that Euan is calling from that place, and I am surprised for it is a fair way from where we now are, across the river and downstream. If he is indeed calling from Mungwezi, then he and Zondani have walked a considerable distance. Taking into account that they would not have been walking as the crow flies. Rhinos do not usually walk in a straight line, though they could if they wanted to!

Although we are not certain, we can only suspect that a rhino has been darted. It is imperative, therefore, to make haste. After a period of time has elapsed, it becomes dangerous to keep an animal sedated with M99, the drug in question. On operations of this nature it is often stressed that ‘alacrity prevents tragedy’. Soon the vehicles are hurtling down a narrow winding bush road at an alarming speed, thankfully depriving the slower moving mopani flies at the same time. Shortly we arrive at the old drift on the Chiredzi River. The Land Rovers power through the sand and shallow water, throwing sand, mud and caution to the wind, before lumbering slowly up the steep incline of the far bank. We are now on Mungwezi and soon back up to full throttle, pedal to the metal. At one point, on high ground, we stop to radio Euan. The reception is greatly improved and we get a good understanding of his whereabouts, before pressing on. After speeding a few more kilometres along the Mungwezi centre road (I am reluctant to entitle it a main road as I do not believe it can legitimately be referred to as such), we turn onto a truly primitive track and are forced to reduce speed considerably. Then the track peters out totally and we bounce through the bush for the remainder of the distance. It is not long before we meet up with Zondani, anxiously waiting.

Whilst we are off-loading the equipment, Zondani hurriedly briefs us. They had tracked Walter all morning, he says. The spoor led them on a confusing circuitous route around number 4, on the Ruware side, for much of that time. It was nearing noon when they discovered that he had crossed the river onto Mungwezi. It had taken them a further two hours to locate the bull in some heavy bush along a small tributary of the Chiredzi. Because of the vegetation, it had proven difficult for Euan to manoeuvre into a position conducive to making a telling shot. Eventually he felt comfortable and made a good shot on the rhino, hitting it squarely on the shoulder. The rhino had charged off, blundering headlong like a tank through the undergrowth. That is when Euan had radioed us. After settling down for a few minutes to give the drug time to act, the two men began their follow up. Following the swath left by Walter’s flight path through the long grass was done with ease, and soon they came up on him plodding sluggishly along, the drug beginning to seriously work his system. At that point we had made contact from the high ground and Euan had dispatched Zondani to meet us.

Zondani has left Euan watching the rhino a short distance away. Lugging the chainsaw, coils of rope, veterinary box and other gear, we cover the rough ground as fast as possible. Surmounting a low ridge, we trot down a rugged rocky slope into a bush-clogged valley below. After following the tributary upstream a short distance, we meet up with Euan. He is monitoring the rhino’s actions intently, for Walter is displaying extreme tenacity and is not yet down. Although completely unconscious, Walter’s legs refuse to give way. Obliviously he high-steps along – sleepwalking. Fortunately his bumbling progress is leading him away from the thick stuff into an area of relatively open mopani woodland. Euan is concerned, that much is apparent. He says that more than enough time has elapsed since the moment of impact and that we cannot afford to wait any longer, we will have to rope and drop the sleeping rhino. Now, whilst it is true that Walter is totally removed from this world, I still find the prospect a daunting one. It goes against all my natural instincts to even approach (let alone tackle) a rhino, sleeping or otherwise!

Now I am placed in a serious predicament, as I am not keen on losing face, either literally or in a figurative sense. Not wanting to expose my cowardice – especially with pretty Sally present – I manage, by employing great willpower, to hush my dissenting voice. I realize that I have little choice in the matter, and so I throw in my lot with the rest of the ‘African cowboys’ and begin rigging up a lasso of sorts. The group spreads out and approaches cautiously from the rear. I do not spread too far – doing so would cause me to lose the semi secure feeling created by the cluster effect. Leading from the front, Euan reassures us that there is nothing to fear. These words of encouragement prompt Sally to shift up a gear and join her mentor at the frontline. Horrific visions of her premature demise flash momentarily through my over imaginative mind. We are gaining ground on the aimlessly ambling rhino, the more courageous members of the group now drawing perilously close to Walter’s ample rear. The front between the frontline and the rear diminishes to frightening nothingness and, as if prompted, Walter stumbles and goes down on his knees. The team grasps the opportunity with all hands, swarming the rhino as mopani flies swarm a person. It is soon made perfectly clear that we are less of an irritant to Walt than the mopani flies are to us. He simply hauls himself up and continues plodding along, totally oblivious to the people clinging like ticks to various parts of his anatomy. The ropes come into play and soon we have him lassoed around both back legs and the neck. With people hauling desperately from all angles, we try in vain to trip up the rhino. Dragging us reluctantly along through the brush and clinging thorn scrub, Walt sluggishly plods on. Very little impression is made until someone proposes the ingenious idea of securing one of the ropes to a mopani tree. It is almost impossible to achieve this but, by using all of our combined resourcefulness, we eventually manage to anchor one of the considerable back legs and halt Walt’s progress. Seizing the moment, we quickly rope his other leg to the same conveniently placed tree. Well secured, Walter continues to attempt forward motion with the use of his front legs alone. Unsteadily he sways from side to side, like a drunkard, before toppling over and crashing thunderously to the ground.

Time is of the essence and the veterinary team goes into action with alacrity. Euan covers the rhino’s exposed eye with his battered bush hat, to protect the sensitive retina from the sun’s fierce glare. Issuing rapid-fire instructions to Sally, who is busying herself locating Walt’s pulse, Euan sets about retrieving blood samples. For a moment there is minor consternation as Walt’s reflexes kick in and he threshes about like a downed sumo wrestler. Veterinarians and veterinary equipment are sent flying for cover. The entire tag team leaps onto Walt, ineffectively attempting to curb the involuntary spasms. Pinning Walt for a three count proves to be an impossible feat, and at one stage there is real fear that he may regain his feet. Fortunately, after a brief, one-sided and bruising struggle, Walt’s muscles relax and he subsides once more. The vets resume their work and soon a strong steady pulse is located and the drawing of blood accomplished. It is now time to get on with the actual de-horning. True to form, the chainsaw stubbornly refuses to start. Machinery, particularly government maintained machinery, never fails to malfunction in Africa. Eventually, after much cursing and coaxing, the chainsaw splutters into life. With the help of Dad and Tore, who are steadying Walt’s massive head at an awkward but workable angle, Euan begins sawing. Rob, the trackers and I hover close by, fearing a re-enactment of the subconscious revival of Walt. Thankfully he doesn’t budge again. Sally, ever eager to please her mentor, never falters in her pulse-monitoring task. As Euan toils, all and sundry are showered by chips of rhino horn confetti. It is hard to believe that this confetti is nothing other than solidified hair. Although it is a laborious, time-consuming task, Euan makes good headway. Soon he has removed the large front horn and begun work on the smaller one. Working efficiently and without pause, he takes care not to remove too much horn and thus expose nerve endings. In due course, the job is completed and two neatly rounded off knolls now decorate the de-horned visage of the new look Walt. Less handsome and lighter by a few kilograms Walt certainly is, safer – who knows?

We hurriedly pack up all the equipment and remove the restraining ropes from both the tree and Walt, before ferrying the gear a short distance away, stashing it in a small thicket of brush. By the time we return, Euan has packed the controversial and valuable horn into his multi-purpose rucksack and is readying himself to administer the antidote. A couple of people have brought cameras along and suggest they would like to get some good close up action shots of Walt as he regains consciousness. Permission is granted and, whilst Euan locates a suitable vein, the rest of us locate suitable trees to climb. Some have photographic and visual opportunities in mind when selecting their trees – some have only safety in mind, firmly entrenched in mind. Walt will have a headache when he recovers and will no doubt be one very angry rhinoceros. The differing heights attained by the various individuals are indicative of the diverse extremes of fear experienced. I manage a lofty perch indeed, although amazingly, Chibobo’s effort surpasses even mine. The photographers, who seem to be the bravest of all, are of course doing it all in the name of art. Euan injects Walt and then, unhurriedly assured, makes his way to his chosen tree. He knows how much time he has, having done it all countless times before. Walt took a long time to go down and he takes a long time to wake up, evidently he is not of cooperative disposition when concerning matters of a veterinary nature. Eventually Euan becomes agitated. Believing that something has gone terribly awry, he descends his tree and cautiously approaches the prone animal. Walt stirs and Euan beats a hasty retreat. Gradually, Walt’s wits return. Soon he lifts his hornless head and, blinking his small piggy eyes in confusion, peers shortsightedly about. The strong clinging odour of human being fills Walt’s nostrils and transmits the danger message to his brains primitive receptors. If not instantaneous, the reaction is at least impressive. Walt lurches to his feet and, stumbling and blundering about, searches for a target. The only thing he espies is a mopani tree and he briefly vents his frustration on it. The mopani tree suffers an awful battering, with Walt making repeated short charges and smashing his head into it. The photographers are hard at work capturing on film the most vicious case of head-butting anyone is ever likely to witness. Walt possibly realizes that his headache is not improving and, with no reaction from his adversary, soon tires of the sport. He delivers a final brutal head-butt that would have felled anything but a mopani tree and then, snorting and grunting angrily, trots off into the bush.

We wait a long time before climbing down to ground level. Walt could trot back at any moment and nobody feels like receiving one of those awesome head-butts. The consequences would be dire as none of us have close to the constitution of a mopani tree. Finally, displaying caution and maintaining silence, we descend. Glancing around nervously, with all our collective senses working in maximum overdrive, we slowly make our way to the thicket to retrieve the gear. Then, still silently, we move off in the direction of the vehicles. As increasing distance is put between Walt and us, the country becomes less wooded and feelings of security return. Soon the mood is jocular – laughing and making merry we are, united in our satisfaction of a job well done. We are nearing the vehicles when Euan stops abruptly, simultaneously slapping his forehead with an open palm in a gesture of forgetfulness. He explains that he has neglected to collect the rhino horn shavings. He had intended to do this once Walter had departed the scene and it had somehow slipped his mind. Euan says he must present the shavings to the authorities, as their absence will raise eyebrows. Without hesitation, Rob volunteers both his and my own services. While the main group covers the short distance to the vehicles, Rob and I trot back to recover the forgotten shavings.

It does not take us long to locate the de-horning place, and soon we have collected up all the shavings in our hats and pockets, making our way back to the vehicles again. The sun is dipping low in the west and, though it is not cool, it is cooler than before. Trotting happily along without a care in the world, noisily reconstructing the events of yet another exciting adventure, on what has turned out to be yet another satisfying day in the bush. After a while, we reach a small clearing in the mopani that I do not recognize from before and, whilst in the process of crossing it, I voice my concern pertaining to the unfamiliar terrain. Rob assures me that there is nothing to worry about. He says he is familiar with the area and we will arrive at the vehicles in due course. Seconds later, we have very good reason to worry, as about a tonne (even without the horns) of irate rhinoceros comes crashing through the bush at us.

We are directly in the centre of the clearing when we hear the all too familiar snort, and it stops us dead in our tracks. Turning to face the direction of the snort, we see the armour plated snorter come charging out of the tree-line, as if in slow motion. Over the years I have received much expert opinion regarding reaction when facing down a charge. However, at this particular moment it does not seem prudent to analyse this opinion and we instead opt to implement drastic action. In reality, there is only one option available and that is flight, alternatives do not even enter the equation. Instinct and flashing thoughts of self-preservation control the moment and dictate our actions. As initial shock gives way to panic induced adrenalin overload, we take to our heels and run. We flee headlong across the open ground, dropping our hats and scattering rhino horn shavings and expert opinion as we go. I am reasonably fast over a short distance and now, fuelled by raw terror, I run faster than ever before. Rob’s fuel is obviously more potent than mine, for he outweighs me by several kilograms and leads me by several yards. There is one solitary tree in the entire clearing and Rob beats me to it. In my lifetime I have never witnessed a human being climb a tree with such speed. In an instant Rob shimmies up the tree, attaining a secure position several metres above the ground before I have even reached said tree. Sensing that the rhino is very close and bearing down fast, and not feeling there is time to attempt the ascent, I continue running. Looming up in front of me is a dense thicket of thorn scrub and, without hesitation, I dive head-first into it. Thankfully the rhino thunders past seconds later, his substandard eyesight failing to pick up my high-speed side-step. Then he stops, mere metres from my hiding place. The rhino realizes that the focus of his outrage is no longer in the line of fire, but wonders where it could have gone. Testing the wind with his super sensor nostrils, he quickly ascertains that the focus is still close at hand. Snorting and snuffling, darting back and forth, testing the wind from every angle, the rhino seeks me out. Presently he comes trotting back to the thicket, head held inquisitively aloft, prepared for battle.

Needless to say, I am not ready for battle. I am observing the rhino’s actions from an awkward, partially upside down foetal position, through one eye and a tiny gap in the scrub. Although it must be exceedingly uncomfortable I feel no discomfort, fear sees to that. I am scratched to ribbons from the dive, thorns have pierced my body all over, and my face is bruised and bloody from violent, uncontrolled contact with the hard earth. Although it must be extremely painful, I feel no pain, adrenalin sees to that. The rhino trots up to the thicket and the rush of blood through my veins drowns out the world.

The rhino approaches to within two metres of me, stopping at the periphery of the thicket. He tests the wind and the smell of my fear must be very powerful in his nostrils. Ludicrously, considering my precarious situation, I positively identify his de-horned snout as being that of Walter. Turning his head this side and that, peering myopically about and pawing the ground in angry frustration, Walt searches for someone to toss and trample. I remain frozen with fright for what seems to be an eternity, but can actually only be seconds. Up in the tree about ten metres away, Rob Style decides to exhibit what he considers to be his wonderful sense of humour. He asks in a loud voice how things are going and why I am being so abnormally silent. And then Rob laughs loudly at his own warped merry-making. Fortunately, the alien sound of voice and laughter perturbs Walt somewhat, and he backs off slightly. Seeing the positive effect his voice has, prompts Rob to begin shouting at the rhino. Clearly disturbed now, Walt retreats further. And then, spinning around with amazing agility, he huffs and puffs and blunders his way across the clearing, disappearing into the mopani. Once I am certain he has gone, I breathe out.

As Rob walks slowly, and I hobble painfully back to the vehicles, we remain aware. There is no banter now. My heart-rate gradually shifts down and eventually returns to idle. I think of how I shall never again believe the tales of how ungainly and cumbersome rhinos are.

The black rhino population in the Chiredzi River Conservancy has, over the years, gone from strength to strength. In 1985, eight sub-adult rhino were introduced to the area; by the year 2000 these had increased to a healthy population of twenty-two. This is, as far as percentage increase is concerned, the greatest success story in the history of Zimbabwean black rhino conservation.