| David_Hulme |

| (.275 member) |

| 04/04/07 05:46 AM |

|

|

[image]

[/image]

[/image] TWO SEASONS IN THE LOWVELD

The 1992 drought was the worst ever experienced in the Lowveld, all the old timers will tell you so. Totally underestimated to begin with, that drought would eventually threaten the existence of our entire area. Animals died in their thousands, both domestic stock and wildlife. Dams and rivers dried up and crops failed totally. People were retrenched from jobs due to economic hardship, and many of them left the Lowveld forever. At the end of the day, the Lowveld only survived through the kindness of outsiders and their donated aid. Yes, the 92 drought was certainly a time to remember…….

“It is not going to rain this year,” says Dad. “Everyone is clinging to hope but it is already too far gone. This is going to be a major disaster to say the least. The cattle are losing condition fast and I have already found dead warthogs. The warthogs will always be the first to go you see, followed by the rest of the grazers. I suspected something was amiss when the impala didn’t lamb, and when the old men warned me to expect a bad season. Some of these old mdalas are far more reliable than satellites and weather forecasters you know. They’ve been talking about drought for some time now and they are right, as usual. I tried to ignore them initially, also clinging to hope I suppose. Now I am certain, we are in for a serious drought. Just look at how low the dam already is? It has never completely dried up before, but this year it definitely will. We’ll have to look for some borehole sites soon. I wish Ian was still around, he was the best water diviner I ever came across. Yes,” says Dad, thoughtfully nodding his head, “this is going to be a major disaster.”

Sipping tea with my family on our veranda, overlooking the puddle that Chehondo has become, I fail to grasp the enormity of what Father is saying.

Not long after, I do begin to grasp the enormity of the devastating drought, as does every other living thing in the Lowveld. Brown much of the time, the Lowveld now takes the colour into a new dimension – a browner shade of brown. Even the ravine turns brown as ground water levels drop alarmingly. Grazing becomes scarcer and Dad sells off the Ruware cattle herd, keeping only twenty or so blood bulls, for restocking someday, maybe. Dad is wise to sell, others hold on to their stock, still disbelieving of the disaster faced. They shall pay a dreadful price later in the year when the Zimbabwean beef market crashes and one cannot give cattle away. Little does anyone realize at that early stage, but the drought shall eventually become the final nail in the coffin for the Lowveld cattle industry. The 92 drought will always be remembered as the turning point – undoubtedly the most influential factor in the transition from cattle ranching to wildlife. Although, Dad and others have been calling for change a long time now, since well before the drought.

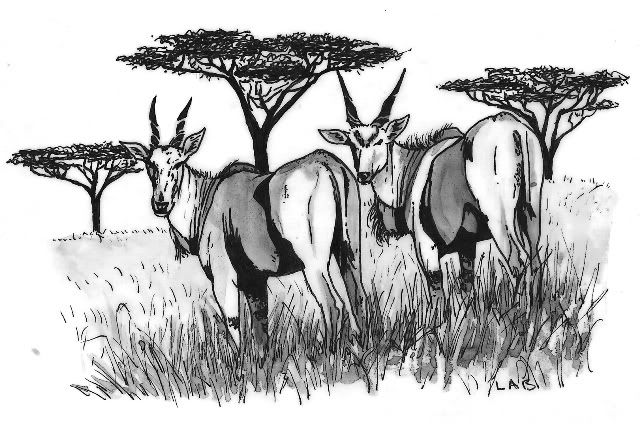

Wild animals begin to die in their droves and local ranchers make desperate last minute efforts to save representatives of all species. Dad builds a huge boma holding facility close to Chehondo, which will eventually hold four hundred plainsgame animals. Eland and sable, zebra and wildebeest, kudu, waterbuck and impala, even a few bushbuck are somehow captured. Dad and the Ruware guys spend many weeks working with a local game capture unit, rounding up as many animals as possible. The most common method of capture is to drive herds by helicopter into temporary bomas, from where they can be handled into more permanent lodgings. I naturally find time to sweet talk the helicopter pilot and am subsequently invited for a spin. Afterwards, decidedly green about the gills and silently mourning a shattered childhood dream, I vow never to fly in a helicopter again. It seems game-capture flying is a hair-raising occupation which requires great skill and meticulous precision. For the life of me I cannot figure out how we miss some of those trees! Though it is difficult to record this, I do squeal a couple of times whilst approaching seemingly inevitable impact at express pace. Back on blissful ground level, the pilot (a good-natured soul) assures me that he won’t tell anyone about the squealing, and thereby ruin my chances of remaining a teenage hero. I thank him kindly and tell everyone else how thoroughly I enjoyed myself but no, I wouldn’t like another spin. I suddenly appear to have found all sorts of more important activity to get on with. After all, one has to forge some kind of realistic future for oneself, can’t spend all day spinning around in a helicopter hey?

Although a healthy breeding nucleus is eventually secured and flourishing, lack of finance obviously dictates and thousands of unlucky un-captured starve in the bush. Added to which, the capture of certain animals would be an exercise too mammoth to entertain, like the hippo for example. Dad saves as many of these un-captured as he possibly can, by establishing feeding points at suitable places throughout the ranch. Many hundreds of animals are saved in this fashion. This feeding exercise would never have been possible without the help of our brother farmers in Zimbabwe’s highlands. There is nothing to feed the animals in the Lowveld, and the Highveld farmers, having been less affected by the drought, donate huge quantities of fodder. The general consensus in the Lowveld is that God should bless these kindly folk, for they too are experiencing serious hardship. The hippos obviously have the most impact on the fodder supply. Tons and tons of hay, sugarcane tops and molasses are trucked in the ‘Blue Bomber’ (Land Rover) to the Chiredzi River on a daily basis. It is very depressing to see the hippo and crocodiles piled on top of each other in the mud pools of the stagnant river. Very depressing indeed, but not the most depressing thing about that drought.

Animals are literally keeling over in the bush, without the energy to rise again. Whoever takes a drive or walk takes a rifle along – an executioner’s rifle. I lose count of how many animals I shoot, stilling their agony forever. It is a grisly job and the prevalent mood is a bleak one. There are orphaned young everywhere, kept alive until now by their dying mothers feeble milk supply. We catch what we can and deliver all and sundry to my mum and sister, who are experiencing their own unique ‘drought toil’ at Chehondo.

Mum and Janna have opened a full-blown and very busy wild animal orphanage in our garden at Chehondo. Here can be seen a diversity of wild animals hard to imagine. Almost every buck is represented, as well as warthogs, bushpigs, civet-cats and tortoises. Janna feeds a bunch of monkeys throughout the drought and they become unbelievably tame for many years after. Those monkeys recognize and love Janna and they never forget her kindness. Whoever said animals are not capable of discerning thought? All and sundry begin weakly drifting in to Chehondo for food as hardy survivors in the vicinity realize what is going down. The eternal barrier between man and beast, the barrier that must be, is temporarily put aside during that terrible time.

‘A zebra and bushpigs in the lounge, you can’t be serious!’

‘No really buddy, got to see it to believe it, those Hulmes are little better than

wildlife themselves!’

Actually, many lowvelders are doing exactly the same thing as we.

A daily task that keeps some of us busy for a time during the drought is tracking and catching crocodiles that leave the shrinking dam in vain attempts at finding greener pastures. No, this is not a work of fiction. Years later, I would watch Crocodile Hunter on satellite television and discover exactly how crocodiles are supposed to be caught. I wish we had Crocodile Hunter assisting us during the drought, but since we didn’t, want him to know that we were catching crocodiles well before he was. Or were we just late getting satellite television? I reckon so, almost as late as it gets surely? The Zimbabwean Lowveld probably beat only rural Afghanistan in the global race for the dish – then again, probably not. Anyway, crocodile catching days usually go something like this.

We rise very early in the morning. The constant heat is almost unbearable these days and it is difficult to sleep any time, let alone when the sun comes up. With sweat dripping, I drink tea with Dad whilst we wait for the guys to arrive for work. Mum and Janna are also already up and about, seeing to the many orphans that need seeing to. When Simon (Dad’s trusted right-hand man) arrives, he and I and a couple of assistants make our way down to the muddy mess that the dam has become, we are the croc team. Once at the ‘pool’, we search for crocodile tracks leading away from the sludge. Initially, crocs were leaving occasionally, one at a time. Now, as instinctive desperation kicks in, several leave every night, searching for never found water. Speed is of the essence if we are not to lose any crocs to the blazing sun. Fortunately, tracking is a simple affair over the grassless ground and the crocs are mostly in weakened condition. Usually we come up on them quickly. And then the hard part begins.

On the day in question, one of the migrating crocs in question opts to enter an old warthog burrow, that was once an old antbear burrow, making it a croc burrow and, when it leaves, an old croc burrow as well. This croc-burrowing scenario often presents itself, the dehydrating crocs seeking shelter from the burning sun and backing themselves into the cool of any convenient hole. In this particular instance however, we are dealing with a fairly big critter, close to ten foot I guess. Simon is our world’s champion croc catcher, our world not yet having heard of Crocodile Hunter. We would not hand over the title even if we had heard of him. After all, how can a non-African be the world’s greatest crocodile catcher? Ludicrous thought really – do they even have crocodiles elsewhere? Anyway, Simon is our champion and it is toward that man that all confused heads turn.

“There is nothing really to do,” says Simon, “except to do what we always do, rope it and pull it out of the hole.”

Wise counsel from the world champ – ingenuity personified. Hissing angrily from its tight fitting earth cocoon, the croc disagrees with the game-plan. Simon, who is a lassoing legend, does not tolerate disagreement and, with noose lightly looped over the end of extended ‘approach’ pole, he goes into action. The plan is to rope the croc around its protruding snout and haul it from the hole, before throwing a sack over its eyes and securing it. In theory it is a simple routine to follow, but things have been known to go horribly awry before, with much smaller specimens than this particular brute. However, it is not long before Simon has the croc’s jaws lassoed together and we are hauling for all we are worth – four men and a crocodile, playing tug of war in the middle of the bush. Well, this is Zimbabwe after all.

Although we fail to budge the croc, it soon becomes irritated and comes boiling from the burrow. Well drilled by Simon beforehand, we all break in the same direction, trying to keep the rope taught and the croc away from us. The croc then breaks in another direction, heading away from its tormentors. Shoulder joints resultantly take strain. One or two fellows go down in the dust but Simon holds on defiantly. Rodeo? We’ll show you rodeo my cowboy friends! And without any horsepower either! The croc drags us around for a while but soon tires, bringing about the moment that Simon has been waiting for. Leaving us holding the rope, he initiates a blind side stalk on the croc, sack in hand. ‘Sacked’ crocs almost always chuck the sack away angrily on the first few attempts, and this specimen does so on more than a few attempts, chucking sack and pulling on the rope powerfully each time, before settling down once more. And then Simon begins over, approaching from a revised blind-side, angle of approach wholly dictated by croc focus zone. Man and croc dance about the bush for a while, before the reptile finally resigns itself, lying still under Simon’s blindfold – shucking chucking, or so it appears. Simon advances cautiously, with me and another assistant at his shoulder. Actually I am not at his shoulder, more like a few safe metres back. We have left only one assistant on the rope but are not too concerned for we always proceed in this fashion and the croc seems tired. ‘Although,’ I think to myself as we approach the prone beast, ‘it is an awfully big croc, bigger than any we have ever roped before.’ Simon lowers his practiced hands slowly, before clamping them over the sack and around the harnessed jaws from behind, simultaneously dropping his weight onto the croc’s upper body, attempting restraint. This is the way to do it. Usually, the croc in question will thresh confusedly around a little, before heavyweight backup overpowers it completely. Snapping is always tried but, well, with noosed snout and temporarily blinded, the struggle is most often a brief one, in favour of the humans. On most occasions, the only things to avoid receiving are croc head-butts or croc tail flicks. On this occasion however, it is not a brief struggle at all, soon swinging alarmingly in favour of the crocodile.

We have left only one bloke on the rope and it is a mistake that is to be deeply regretted. After this incident with the ten-footer, we never again try to restrain such a large croc with only four men. From then on we play it safe and double up on manpower. Sadly, on the day of the ten-footer, we have not doubled up. Added to which, two of the three assistants (myself not included), are new boys on the block. Totally green croc-catching novices – dark green in fact.

The ten-footer does not react in the way roped and sacked crocs are supposed to react, and it doesn’t just offer token resistance either. Responding immediately and very aggressively to Simon’s attempt at pinning it to the dusty canvas, it instantaneously achieves frenzy, flicking its substantial tail dangerously about the place. An untrained and nervous back up team fails to efficiently back-up, and Simon does not take too much of a beating before he wisely separates himself from the crazed croc. Simon has been croc bitten on the hand before and it was obviously an unpleasant experience. And that was by a five-footer, this croc is double the size and a bite from it will cause far worse than just hand damage. Simon and sack are thrown off contemptuously and the crocodile can see once more. What it sees does not make it a happy croc – human beings scampering about close at hand, trying to depart the danger zone. Although what it sees does not please the croc too much, what it feels perks it up a little. It feels slackness on the rope holding its jaws together – feels slackness and senses liberty. The novice croc cowboy on the rope has completely neglected to maintain any semblance of a rein on proceedings, dumbstruck and awed by the unfolding events – the raw display of sheer croc power. The noose slips off and the croc comes bombing over the ground, low level flying, straight towards us!

Now, I have experienced a few croc scenarios in my life, but I have never been blatantly croc charged over land, or in the water for that matter. I should imagine that most people who have been croc charged have been in water, or close to it anyway. Either way, the vast majority will never be able to tell us of their ordeal. As we scurry for safety in the face of the oncoming croc, I wonder how it will drown whomever it catches. Does it not realize that there is a serious drought in progress and no water for miles around? I don’t really think those things as I bolt, but wanted to write them anyway. If I am thinking anything at all it is ‘let me get out of here in a hurry!’ Seconds later, hopes of future croc charge tales are dashed as the croc rushes straight past us, launching itself headfirst back into the old warthog burrow, once again making it a croc burrow. Simply seeking refuge – tired of the harassment.

Now we have a serious predicament on our hands. It is one thing to pull a croc out of a hole by harnessed snout, a totally different ballgame to pull it out backwards by the tail. Obviously the croc would come out snapping and spinning, creating a dangerous situation, most dangerous indeed. The other alternative is to dig for its head from above, a long and involved process that has problems of its own. Plus, we have no digging tools and the house is some distance away. Simon is the decider and Simon decides.

“We will pull it out,” he says. “We have two more ngwena (crocs) to follow and it is getting very hot.”

The two dark green assistants nod numbly, unaware of what they are agreeing to. I maintain silence for it is not correct to question experience. I just begin shaking a little. I have done this before with much smaller specimens and have an idea of what is to follow. After catching a little more breath, we rope the croc’s tail. Then the two gophers and I take hold and begin hauling, Simon standing close by with lasso rope and sacking. Fortunately, one of the gophers – possibly eager to please but more likely imagination devoid – is closer to the croc than I. Predictably the reptile fails to budge – it shall, once again, have to be irritated from the burrow. The advent of irritation is not too long in the coming. Back-peddling from the burrow at pace, the enraged croc begins careering around the place, in a total snapping fury. Needless to say, it is not long before the rope is abandoned and heel taken to. This is now truly the first time that I have been charged by an intent croc. Still, all the intent in the world is soon negated by low energy levels and the exhausted creature pulls up short. Simon has somehow retained focus and he now sees and grasps his opportunity. Getting in close, he briefly sizes the target up before going into action. One practiced toss and accompanying jerk, and the croc is again snout roped. I rush quickly to Simon’s assistance for he is seriously outweighed. The second and third assistants take the hint and also add their weight. The struggle is not too extreme this time and the croc quickly tires, running on very close to an empty tank now. Simon carries out the blindfolding and the croc does not so much as move, totally spent. The antics of the past half hour, added to the heat and its lack of nutrition lately, have worn out this crocodile completely. We take total advantage and, before long, both croc and operation are securely wrapped up. Fortunately there is no blood this time, but for a couple of grazed kneecaps. Shortly afterwards, I bring the Land Rover up and we load our captive, before transporting it to Dad’s borehole fed, makeshift croc ponds, below the dam wall. Then we go after the other two escapees. Thankfully they turn out to be smaller, less physical specimens.

All through that long year, the burning sun hammers the land relentlessly. Energy sapping and soul-destroying high temperatures are the order of the year, night and winter bringing little, if any, respite. Established hardwood trees begin dying on a scale never known before. The old timers say that this is so and who is one to question the mdalas? On occasion I see birds dying in flight. Okay, maybe they don’t die in flight, but they certainly lose consciousness and direction in flight, dying shortly thereafter. Once, whilst having tea on the veranda, the whole family (besides Jonny who is in the Zambezi Valley hunting as usual) witnesses one of these tragic, exhaustion induced aerial nosedives, not twenty yards off, on what is left of the lawn. The bird in question is a roller of some sort that fails to flutter from one leafless tree to another, a few metres away. And then follows the last flutter and the rolling nosedive. Actually, it is more like a belly flop. Exaggerated shrieks from Mum and Janna predictably ensue, followed by futile resuscitation attempts. Although I don’t want to make too much fun of this particular bird’s needless death, it is but one amongst thousands of dead and dying creatures. After all, the rollers probably won’t become extinct now will they? Janna buries the roller down by the vegetable garden, alongside many other drought victims, once she is certain there is no hope. Water and food are generally non-existent out there in the bush, and it is only the animals that come across water and feed points that are able to survive. Although Dad manages to continue pumping enough borehole water to vital areas throughout the drought, as the months drag on he is forced to cut back significantly on feed. Even the Highveld is running out. This drought has now become the most devastating in the country’s entire history, unprecedented suffering.

Obviously, people are also affected by the drought. Although the Ruware workers are well fed, it is not long before food supply in the tribal areas dries up. A massive food distribution initiative ensues, spearheaded by international humanitarian groups, local NGO’s and commercial farmers countrywide. One cannot praise Zimbabwe’s commercial farmers enough in this time of national crisis, particularly the Highveld crop growers. Backs to the wall themselves, they pull out all stops to save our nation. As a result of this unselfish approach, the country does not die completely and, more importantly, very few Zimbabwean people die. Although much is lost during the drought, a positive and relatively well-nourished populace is ready to begin repair work when it finally comes to an end.

Pencil has much to say regarding the drought.

“The spirits are displeased,” he says. “And there is good reason for their displeasure. It is because of the youth, the youth of today. Young people in this country have totally lost sight of value and tradition. In my day, one would never get away with the weakness so apparent amongst today’s younger people. For us, there was hunting, fishing, raising cattle and worship. These days it is women, transistor radios and beer. In the past, much time was spent communicating with the ancestors, giving thanks and making offerings. Rain obviously played a big role in our lives then, as it does now. In those days we held special rain ceremonies, well before and leading up to the rain season. Should the rains fail to arrive, we continued requesting, for as long as it took. Although we still experienced bad seasons due to various factors, we never experienced anything like this. Now the spirits are very angry, angrier than I have ever known them to be. This is because there are so few of us old men still attending the rain ceremonies, because of the absence and ridicule of the many unbelievers. Mware has told us so, us few remaining faithful.”

Pencil often carries on in this vein for some time, to anyone who cares to listen. As always, I care to listen. Though I am very much a part of today’s wayward youth, I know that what the Old Man says is true, for the modern world is full of scepticism and unsubstantiated opinion. Even inexperience can appreciate this stark truth, once it is explained by wisdom, once the ways of old are made known. It is all so much more complex than the ‘two cells fused’ sprouting of the supposedly informed isn’t it? The Old Man believes and, therefore, I also believe.

The talk is that there shall be another rainless summer. Of course, that would be the end of the story, literally. As November gives way to December and the skies remain devoid of cloud, a fair amount of expectant strain is taken by all and sundry. Shortly before Christmas, I am chatting with the Old Man down at the dam when, out of the blue, he tells me that the negative rumours have no foundation whatsoever, that the rain is not far off. The Old Man explains that the spirits do not wish to totally destroy the land, it being their own creation. No, the spirits are simply sending a warning, albeit a harsh one, a warning for the errant.

“It is truly amazing,” says the Old Man, “how profoundly influenced so many people have become by the hardship experienced of late.”

How difficult it is to try and describe the Lowveld when the rains finally come. The initial downpour arrives on Christmas Eve and it is the most wonderful gift any lowvelder has ever received. Every living creature frolics joyfully in the welcome relief that that rainstorm brings – long into the night, greedily drinking in the pure smell of a brand new beginning. The next morning the Lowveld is breathing again, but obviously not yet in stable condition. The storm has caused some runoff and allowed several rivers to flow briefly, but the parched earth has conclusively sponged up most of the water. Pencil says that it will take several such storms before much of an impression is made, for the earth is very thirsty. Those storms are not long coming, and a few weeks later the Lowveld is stabilized, teetering weakly on the long road to recovery.

The animals take the coming of the rains celebration into a new dimension. Emaciated beyond belief, hardy bush survivors cavort and flick their heels over the matt of fresh green grass that unbelievably takes. Who would have thought that any seed could survive that type of treatment? All over our dead lawn and down on the floodplain, the bottle-fed orphans dash this way and that, frolicking and skidding about in the unfamiliar mud. For them the occasion is extra special, as it is the first time any of them have experienced rain at all, and some are close to two years old. The dams fill and one day we release the crocodiles back into Chehondo. They swim far down, deep into the muddy water, before breaking the surface and diving again. Over and over they dive and rise, persistent in the rediscovery of their forgotten underwater world. The frame of mind in the bomas reaches fever pitch as Dad delays releasing animals, until he is satisfied that the rain is here to stay. Eventually he does release them, and there is thundering pandemonium as every animal attempts outdoing the rest, covering as much ground as possible in as short a time possible. What is most memorable to me about the Lowveld’s rebirth are the sounds, the remarkable diversity that is bush sound, the sound that has been absent so long. All through the day and all through the night, as the creatures convey their thanks and unbounded joy to the world. Snorting, grunting, squealing, neighing, barking, coughing, chirping, croaking, chattering and many, many more sounds. The marvellous music of the reborn bush.

Of course, the drought does not really end with the coming of the rain, there is still much to do. Animals still have to be fed for a considerable duration, as the bush takes time to recover completely. This alone keeps all hands extremely busy. Dams are restocked with fish and, because of the Lowveld’s incredible fertility, these fish breed up quickly. It is not long before the crocs are back gorging in the thick of fish shoals. All in all, the bush recovers in miraculous fashion, soon restored to its former glory. Only the dead trees and the scarcity of game are stark reminders of what was, a short time before.

A couple of months later, I am whiling away the late afternoon down on the rocks overlooking the dam. It has been raining almost consistently of late and is showing no sign of abating. The dam is almost full again – the contrast between now and then phenomenal. Leaves adorn the living trees and lush grass has covered the bare earth remarkably. As darkness descends, I make my way slowly homeward, accompanied by the sounds of a lively Chehondo evening. Down by the dam, the croaking frogs dominate. As I walk further from the water, the insects take over the leading role. A far ranging myriad of exquisitely pitched resonance, trilled out by a million mandible-wielding songsters, bringing the night alive with the addictive euphony of nocturnal Africa.

The drought’s aftermath brings about some very strange happenings, the most notable of these being plague. First come the rats, followed closely by bullfrogs and quelia birds – thousands upon thousands of each, hundreds of thousands, millions, unparalleled population explosions. Raptors perch in the treetops above quelia bird colonies for weeks on end, feasting constantly on the tiny birds and flourishing. The juvenile bullfrogs turn cannibal and begin feasting on each other, when their own natural food source runs out. It is quite a disturbing sight to see one frog swallowing another, millimetre at a time, slowly but purposefully. And size is irrelevant to the swallowers, who are sometimes far smaller than the swallowed – mind blowing stuff. Throughout the drought the predators flourished, feeding well off a never-ending menu of dead or dying. In the immediate aftermath, with game very thin on the ground, predators too come under pressure, losing condition and dying. Boom and crash – the law of the land, the balance of nature.

During the drought my mother adopted two newly born eland on the brink of death. Against the odds, Mum bottle-fed and reared the two orphans to health and they went from strength to strength. The two eland were male and female and were named Moffu (eland) and Olivia respectively. Firm favourites of Mum’s, like all the other orphans, the eland were eventually reintroduced to the bush and went on their way. Although occasionally seen by Dad or the game-scouts, the two eland obviously adapted well to their new life and were gradually seen less of.

One day, about two years or so after the drought, during a break from my job in the Zambezi Valley, I am taking some visitors on a game drive around Ruware. Amongst the visitors is a very pretty young lady who I am trying my utmost to impress, and getting nowhere in a hurry. As we drive along, after I have all but given up on pretty face, we see two eland browsing about eighty yards away, in the middle of an acacia sprinkled mapari (open area). Although game has generally bred up well since the drought, numbers are nothing like before and seeing eland is still a rarity. I pull up so that everyone may have a good look at the two splendid representatives. We watch the eland for a long time and everyone coos and clucks accordingly. After a while, I began to think it strange that the eland are not moving away from the intrusion, that they continue feeding unperturbed. And then it dawns on me and I alight from the vehicle, beginning a slow approach. The eland monitor my approach but do not spook and this makes me certain. In the vehicle, the cooing and clucking gives way to total silence. Sixty yards, forty yards, twenty yards, and then I slow right down, softly speaking to the curious eland as I cover the last few yards.

“Okay Moffu, okay Livy, it’s only me,” I say gently, voice pitched low.

Making soft sounds of encouragement I continue forward, ever so slowly. As the almost fully-grown eland bull accepts the overture and reciprocates, hesitantly taking a couple of steps towards me, I feel the stunned onlookers in the vehicle eighty yards away. As Moffu comes closer and nuzzles my outstretched hand, even I am stunned – it has been two long years after all. When Moffu lowers his massive head and thick spiral horns, presenting his matted ruff for a thorough scratching, even Olivia is stunned. Yes, of course things go more smoothly with the pretty girl after the eland encounter.