NitroX

|

| (.700 member) |

| 03/04/22 02:35 AM |

|

|

|

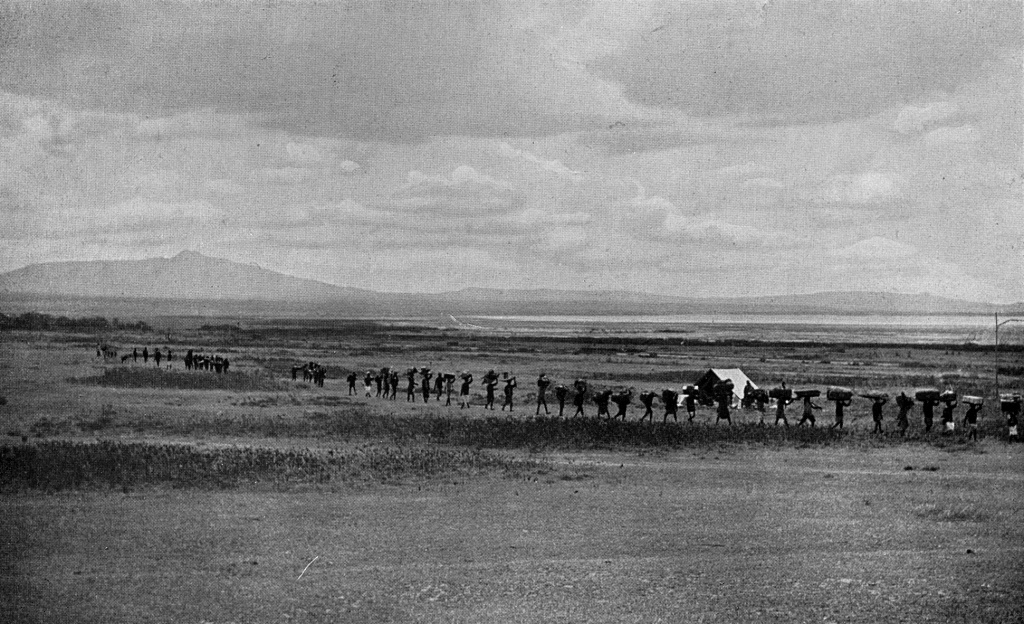

On Safari

long line of people walking

Safari on the march

From Abel Chapman, On Safari: Big-Game Hunting in British East Africa, with Studies in Bird-Life (Edward Arnold, London, 1908).

Photo: R. J. Cuninghame

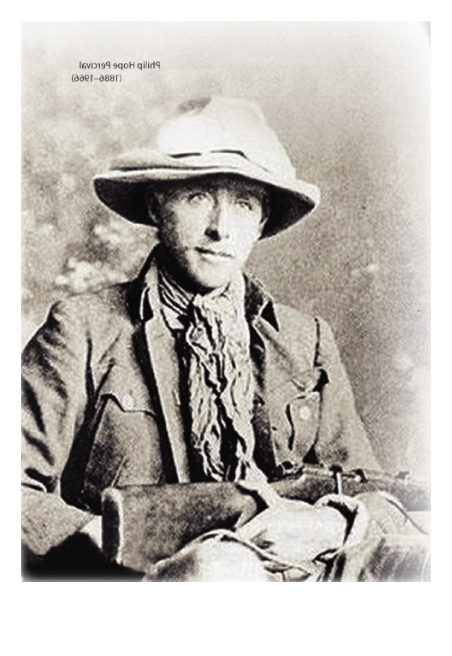

A trip to Africa in the early part of the 20th century was not one to be undertaken lightly (or cheaply). Months of planning went into organizing the logistics of how to get there, what to take, and what to do upon arrival. Safari outfitters, such as Newland, Tarlton & Company and Boma Trading Co., with offices in both London and Nairobi, helped make the job easier by supplying almost everything a hunter or naturalist needed in the way of camp equipment and food supplies. They could also arrange to hire porters, guides, armed security guards (askaris), gun-bearers, cooks, and “tent boys,” as well as a “headman” to supervise them all.

old advertisement for a safari outfitters

Ad for Newland, Tarlton & Co.

From H. F. Ward and J. W. Milligan, Handbook of British East Africa (The Caston [B.E.A.] Printing & Publishing Co., Ltd., Nairobi, 1912).

Frick's personal library included a large collection of books about Africa and the adventurers who journeyed there, and many of them offered advice on travel itineraries and equipment lists. Percy C. Madeira's Hunting in British East Africa (1909) included a “List of equipment from England for two persons for one hundred days safari.” In addition to basic camping supplies and food, Madeira's essentials included chocolate, brandy, and Scotch whiskey.

The costs of going on safari meant it was largely a pursuit of the privileged classes. In The Land of the Lion (1909), W. S. Rainsford's estimate was $500 a month for an expedition of three to four months for two people and about 60 porters, but not including food for the sportsmen, guns and ammunition, hunting licenses, customs fees, and railroad travel. This translates to well over $10,000 a month in today's money. Additional costs could be incurred for longer trips into more remote areas, not to mention the expenses of preparing, packing, and shipping trophies home.

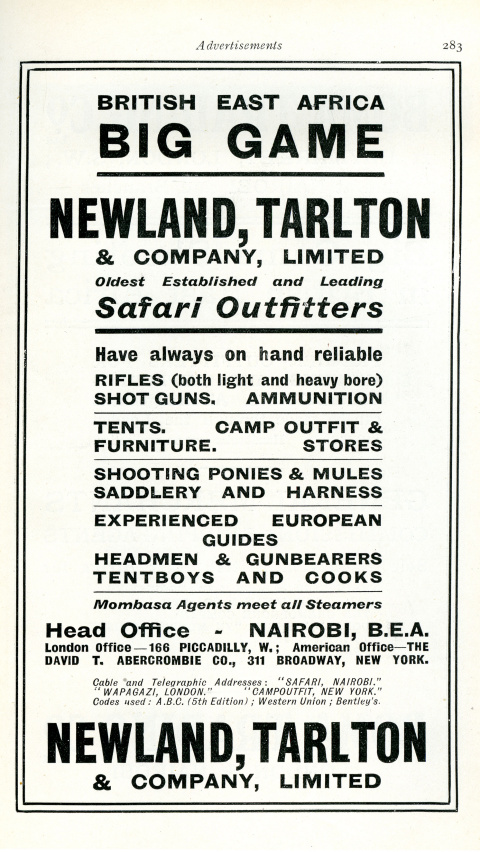

Ad for Humphreys & Crook

From H. F. Ward and J. W. Milligan, Handbook of British East Africa (The Caston [B.E.A.] Printing & Publishing Co., Ltd., Nairobi, 1912).

A typical day on safari meant breakfast by candlelight, heading out before dawn, and reaching the next camp by mid-day in order to avoid the strong afternoon sun. The distance covered varied considerably, depending on the terrain. A twenty-mile hike would be considered a pretty good day, but twelve to fifteen miles was probably more common. The porters, most carrying 60-pound loads, were skilled in quickly setting up camp, and each had a specific duty to attend to whether it was tent-pitching, unloading provisions, or gathering firewood and water.

If an army is said to “march on its stomach,” it might be equally true for a safari. The contentment of the crew and their ability to function efficiently could well depend on the availability of fresh meat. Fresh fruits and vegetables were scarce, but game of some kind could usually be found to supplement the tinned and dried staples and the porters' daily “posho” (usually grain of some kind and possibly rice and/or beans). Game meat was often tough and stringy, and sometimes hours of boiling failed to make it palatable. The natives, with decidedly different tastes than the Europeans or Americans, were said to be fond of zebra and elephant flesh, usually raw or barely cooked. Rhino-tongue soup, ostrich-egg omelets, wildebeest liver and bacon, and giraffe marrow might be on the menu for the safari clients. A dinner example from Abel Chapman's book, On Safari (1908), included: marrow-soup, cutlets of gazelle, spatchcocked guinea-fowl, curried venison, and marvelous pudding (cornflour from Glasgow, peaches from Australia, or pineapple from Natal), with tea and a final “tot.”

Once a hunter collected his trophies, it was essential to treat the skins and skulls properly before shipping them home. Insects, rot, and unpredictable weather could quickly cause a prized specimen to become unusable for a taxidermy mount. Drying and preservative agents commonly used in the field included wood ash, alum, arsenic, turpentine, and napthalene (found in mothballs). For those who managed to bag an elephant it was especially challenging to transform such a large animal into a transportable package. In Vivienne de Watteville's, Out in the Blue (1927), it took a dozen boys standing on a folded elephant skin, pulling it taut with ropes, to reduce it to a 5 x 6 x 2 ft. cube. The extraordinary weight of the skin required five men to carry it.

Frick donated many of the African specimens he collected to the museum and played an active role in how they would be mounted and displayed by providing dimensions, drawings, and ideas to the preparators and taxidermy artists. With their innovative techniques and attention to detail, chief taxidermist Remi Santens and his brother, Joseph, were renowned for creating lifelike mounts, and their work can still be seen today in the museum's Hall of African Wildlife.

Ad for Burberrys

From C. H. Stigand, The Game of British East Africa (Horace Cox, Windsor House, London, 1909).

Ad for East Africa & Uganda Corporation's Hotels

From H. F. Ward and J. W. Milligan, Handbook of British East Africa (The Caston [B.E.A.] Printing & Publishing Co., Ltd., Nairobi, 1912).

Ad for Wilkinson Sword Co., Ltd.

From H. F. Ward and J. W. Milligan, Handbook of British East Africa (The Caston [B.E.A.] Printing & Publishing Co., Ltd., Nairobi, 1912).

https://mammals.carnegiemnh.org/childs-frick-abyssinian-expedition/on-safari/