| mehulkamdar |

| (.416 member) |

| 13/11/07 12:21 PM |

|

|

|

The Policy Proposal on Which The Madhya Pradesh Hunting Proposal is Based

Mangement of Over Abundant Ungulate Populations

H.S. Pabla

1. Introduction

Throughout human history, man and wildlife have had an intimate relationship. In the beginning, man was a food item for big predators and a competitor for herbivores. With the passage of time, and the advent of tools and weapons, man himself became a successful predator and the herbivores became a resource for him. Seasonal or periodic human migrations were dictated by the animal migrations in search of greener pastures or drinking water. An equilibrium was established, perhaps, when man became a cultivator. His crops acted as a powerful lure for wild herbivores, while man was able to snare, trap or shoot them either in the act of feeding or while they hung around his fields. As bulk of the animals still lived far away from human habitation and the hunting methods were simple, and there was little commerce, the number of animals killed was not large enough to endanger their existence. But with the advent of guns, vehicles and trade in wildlife products, the equation got vitiated.

The explosion in human population in the 20th century pushed human settlements into the remotest parts of our wilderness, so that the entire countryside became a neighbourhood of man and wildlife. As there was little legal protection for animals in the colonial times, except, perhaps, in reserved shooting blocks, wildlife lost its habitat to agriculture and huge numbers to poaching. Official response to this drastic loss came in the form of promulgation of various rules and regulations to regulate hunting. Madhya Pradesh enacted its ‘MP Forest (Hunting, Shooting, Fishing, Poisoning Water and Setting Traps or Snares in Reserved or Protected Forests) Rules, 1963 under the Indian Forest Act, 1927. A more organised response at the national level came in the form of the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972 (WPA) which created a strong framework for directing the future conservation efforts of the country. The Act was founded on the fact that wildlife is a natural resource which could be preserved if consumed carefully. It proposed creation of a set of graded protected areas, namely national parks, sanctuaries, closed areas and game reserves, where animals were to be fully protected while prescribing conditions under which animals could be hunted and traded in other areas. However, the WPA lost its original character with the passage of time as a series of amendments have rendered it completely ineffective as a management tool and have converted it into a sort of religious scripture prohibiting every worldly benefit that man can possibly draw from wildlife. Rather than creating a system of checks and balances, hunting and trade in all forms, has been banned.

The impact of the Act on the growth of wildlife populations is debatable. While we can say that whatever is left of our wildlife is due to the protection provided by the Act, it also needs to be decided whether we are better off now, in comparison to the situation prevailing at the time of the promulgation of the Act. Thanks to the Act, we have nearly 12% of our forest areas protected under the Act, where the populations have definitely grown over time although we have lost some species even inside the PAs. However, we all agree that wildlife is not better off in our managed forests, despite the protection provided by law.

OVER-ABUNDANT POPULATIONS

This expression is used with reference to situations where wild animals cause extensive crop damage. The perception that there are any over-abundant wildlife populations is not well founded. The notion of abundance is based on the fact that wildlife causes widespread damage to human interests, not based on their numbers. The reality is that wildlife is not at all abundant outside a few high profile protected areas; it only looks abundant on the basis of the damage it causes to our crops, property and life. Only populations of a few species, namely nilgai, wild pig and black buck, which live on agricultural lands, or close by, are seen as abundant. Even these species are not abundant as their density in and around these croplands is far lower than their density in managed forests, not to speak of the PAs.

Whether these populations are abundant or not, they live off the agricultural lands, causing huge losses to the rural economy. The food obtained by the animals from the agricultural lands is clearly the cost of conservation that should be borne by the government, not by the poor farmers. It is clear that conservation comes at a cost but the costs are distributed unevenly in the society. The government bears the limited cost of maintaining the staff and developing the infrastructure. This cost is negligible when compared with the direct and indirect costs incurred by the local people in terms of lost economic opportunities, crop raiding and livestock depredations. For example, in Madhya Pradesh alone, conservation impacts nearly 5,500 villages (within 2 km from forest boundary) with 451,000 families and 8,79,450 ha of cultivable land. Between April 1998 and March 2003, 166 human deaths, and 3131 human injuries from wildlife were reported. In addition, 14090 cattle were killed by large predators. There is no record of the extent of damage to crops which is even more grievous than the losses to predators. Although most states have provisions for paying some kind of ex gratia amounts for the loss of human lives or livestock, very few states have a provision for compensating crop losses. There are neither attempts to estimate and compensate these costs, nor efforts to alleviate these problems and minimise the costs. And wherever any compensation systems have been evolved, these are limited and cosmetic. Due to the inherent conflict between the conservation programmes and the local people, there is little popular sympathy for wildlife. Some urban elite, the environmentalists and the conservation agencies are the only ones who support conservation. The local people want their forests protected but do not want wild animals. It is almost impossible to convince them of the reasons for protecting wildlife, except as a vague righteous belief in the right of all living beings to live. But in the face of the severe economic hardships that these animals perpetrate, even these traditional beliefs do not stop them from killing these animals.

Estimated Crop Damage and Protection Costs

Although no studies on the quantification of damage are available in India, even empirical estimates show that the quantum and spread of this damage is quite astounding. An accurate assessment of crop damage by wild animals is very difficult for various reasons. While it is difficult to distinguish the damage caused by wild animals from that caused by domestic livestock, quantification of the loss in monetary or grain terms is even more difficult without actually cutting the crop in damaged and control fields. A rapid survey, based on interviews with villagers, was conducted in the Noradehi, Raisen and Vidisha forest divisions in Madhya Pradesh in September 2002, to assess the crop damage. The data from Noradehi appeared to be sufficiently reliable to be useful for making state level projections, while that from the other divisions was useful for a general comparison. As per the data received from Noradehi, up to 30%, 10% and 40% loss was reported in case of paddy, wheat and gram crops, respectively, in the villages situated inside the sanctuary (sample: 2 villages, all families covered). The loss in these villages is attributed to nilgai, chinkara, chital and wild pig. In another village, situated about two km from the forest boundary, 10% and 25% loss in the case of paddy and gram crops respectively has been estimated. Here, the list of raiders also includes the common langur. No crop damage clearly attributed to wild animals was found in any village beyond 2 km from the forest boundary. The average crop damage has been assessed to be Rs. 1067 per ha, per year, in the sample villages, which comes to between 10% to 20% of the total yield, depending upon whether the field is irrigated or not and whether it is single crop or two crop agriculture. On the basis of the human population and cultivated area of 214 villages situated within 5 km from the sanctuary boundary and the crop loss assessed in the sample villages, the total loss to the state has been estimated as Rs. 627 crores out of which Rs. 94 crores is the direct loss while the remaining Rs. 534 crores is the cost of protection inputs in the form of labour and materials. Although these figures are rather empirical, but the exercise gives us an idea of the enormity of the problem. It is obvious that the actual damage to crops, coupled with the opportunity cost of protecting the crops is so high that it deserves a serious attention of the state and the society. Equally serious is the loss of quality of life of the people of the vulnerable villages in terms of lost comfort and sleep. Spending close to 100 nights, year after year, perch precariously built machans in cold and wet weather must be a very exasperating experience.

It is obvious from the above that wild animals, both herbivores and predators are a serious issue in the lives of the rural people, especially the tribals and other poorer sections. While predators have to pay the price in terms of poisoning, snaring and electrocution deaths, crop-raiding populations, especially those away from PAs, are also in serious danger of being exterminated through poaching by locals as well as professionals. Unless serious efforts are made to control the prevailing conflict, these populations are likely to be wiped out in the near future. Therefore, the management of these populations should deal with the problem of crop raiding and the conservation of these species as well.

Management of Losses and Populations

There are two possible strategies to deal with the problem, namely, prevention, and compensation. Prevention can either be by putting fences between the animals and crops or by reducing the populations of the problem animals. Compensation can be either on the basis of periodic assessments or at flat rates. These strategies can be used in various combinations, depending upon specific situations. These possible options are briefly discussed below.

Compensation

As crop and other kinds of damage is inevitable where man and wildlife live together, it is the duty of the government to compensate these losses because by feeding the animals on their crops, the farmers are directly bearing the cost of maintaining our wildlife, at least partially. Many governments have compensation schemes in place but generally prefer to call it ex gratia because the amounts offered are not comparable to the losses incurred. A summary of the kinds and rates of compensation prevalent in a few states is given in the Annexure-I at the end.

In most cases, the system of investigations before a payment can be made is so cumbersome that it is hard to imagine any money reaching the affected people at all. Therefore, the schemes are not really serving their obvious purpose of controlling the hostility of the people against wildlife. A more transparent, fair and effective policy can be based on the principle that everybody who lives in a given area is equally vulnerable to these losses and everybody should be paid uniform rates, irrespective of the actual loss. This is because the quantum of loss is likely to be inversely proportional to the crop protection costs incurred by the owner, which deserve to be compensated as well. In such a case, the probability of loss for different villages, or belts, can be assessed periodically through a systematic sampling, and cheques can be sent to the listed people without their having to submit a claim. Obviously, the scheme is going to be expensive. But if the poorest people are already paying the cost, it is reasonable for the government to foot the bill. Though it sounds utopian, such systems already exist in the western countries. It is reported that farmers in Great Britain get paid on the basis of migratory ducks feeding in a field on the day of assessment. No assessment of actual loss is required as the loss will depend on the number of birds feeding in a field.

Fencing

As long as man and animals share common habitats, crop damage is inevitable. It is true that the extent of damage depends upon the density of the problem populations around croplands. The preventive strategies can be based on either keeping the numbers of animals low or fencing the croplands effectively to prevent the animals from entering the fields. In Africa, most of the protected areas are fenced off with the help of a double fence, the inner one being a power fence while the outer one is a chain link fence. In many cases, a road runs along the periphery for patrolling the fence. The fence serves the dual purpose of keeping the wild animals inside while preventing the domestic livestock and people out. However, in India human habitation is intimately interspersed with wildlife habitats, therefore putting fences on forest or PA boundaries may be worthwhile at only very few locations. Another option can be either putting fences around villages or croplands, leaving corridors for wild animals between the fences. Again, as putting a single fence around whole villages may pose many practical problems, private fences involving groups of farmers, with attractive subsidies from the government may provide a more pragmatic solution. In fact, a combination of both the approaches, based on site-specific requirements, will have to be adopted. While chain-link fences are expensive to install but easy to maintain, power fences are relatively cheaper to install but require continual maintenance. Barbed-wire fences can also be a useful alternative if the strands are sufficiently close and tight to prevent animals from forcing through. However, in view of the exorbitant costs of metallic fencing, a heavy government subsidy will be required to popularise such solutions by people in general. A realistic compensation for crop losses and protection costs, along with subsidies on crop protection, is a critical requirement. There are all kinds of agricultural and other subsidies but none of them targets, conservation and agriculture alike. A conservation subsidy to fund such a scheme can go a long way in helping the poor farmers and wildlife at the same time. The estimate of available subsidies is to the tune of Rs. 200,000 crores per annum as reported in the news papers. Diverting some of this money for such a scheme should not be difficult for a large country like ours.

Scale of Poaching

In a study, conducted in 1996-97, published in Ambio, Ulhas Karanth and Madhusudan have reported poaching levels of 216 hunter days per month per village, involving 26 species, around Kundremukh National Park in Karnataka. The same study reported regular hunting of 16 species around Nagarhole National Park. Hunters supply meat to nearby towns in Karnataka and Kerala. If that is the norm for the rest of the country as well, keeping in mind the number of villages situated in the forest areas, poaching must be treated as a bigger threat to wildlife than even the habitat loss. Applying this norm to MP, and presuming that a hunter must be earning at least 100 rupees per day for his work, the poachers are earning around Rs. 600 crore per annum. This is nearly double of the annual revenue of the forest department. If this is an exaggeration, one can apply one’s own correction factor to arrive at an acceptable figure. The loss is still mind boggling. Who are we fooling by putting a ban on hunting?

Population Management

Scientific management of herbivore populations is of critical importance to their well being, as otherwise, the populations may explode and push themselves, and their sympatric species, into extinction, by destroying their own habitat through overgrazing. Population management is all the more important in situations where these populations earn human hostility by damaging crops and other property, as the risk is then compounded by increased poaching. The problem populations outside PAs, where they are in serious conflict with local human interests, are in serious and imminent danger of being wiped out, because they are not wanted there. These populations can only be saved if they lose their nuisance value or turn into a positive resource for the people concerned. Translocation, culling and sport hunting are the only solutions for managing populations.

Translocation

Translocation of wild animals is a routine activity in Africa and other countries where wildlife is actively managed. It is mainly used for trading animals and stocking new protected areas or private game reserves. It is hardly ever used as a tool to manage unwanted herbivore populations because of the scale of operations required. Mass translocation of whole populations is an extremely expensive and slow proposition and is unviable as a tool of choice. Moreover, in India, we have no experience or expertise in handling animals at the required scale and it will be impossible to consider any sizable initiative without intensive hands-on training of a very large number of forest staff. As such training is not available in India at present, collaboration with African or American experts is the only way of introducing it at any reasonable scale. It usually involves high mortality rates which may be unacceptable in the current sentimental environment in India.

Culling

Culling is the process of reducing wild populations by killing. The term is more often used to describe an operation when management agencies themselves, or through hired shooters, kills large numbers of animals, of selected age and sex, to balance the population size, or its growth rate, to suit the available habitat. Culling requires expertise and equipment currently beyond the reach of our forest departments. Even more important issue is what to do with large numbers of dead animals in the light of the legal prohibition against utilising the products of culling for consumption or trade.

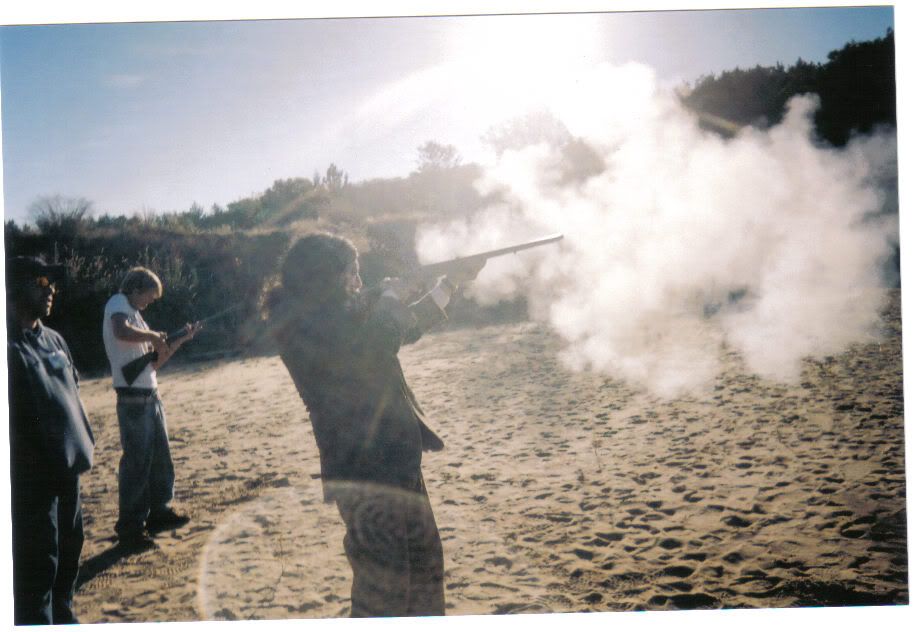

Sport Hunting

Sport hunting, through permits, is the only viable way of managing wildlife populations in the long run. Hunting is one of the most popular recreation activities in the world for which people are ready to pay mind boggling amounts of money. An extreme example of the hunting craze was reported, in The Hunting Report Newsletter (at www.huntingreport.com), when a single Canadian bighorn sheep hunt was auctioned for 4,05,000 dollars. And the hunter, one Sherwin Scott, could not bag the animal within the allotted 17 day hunt in the Cadoman area bordering Jasper National Park. Wild animals near human habitations are being killed by poachers without paying anything. If we officially harvest the animals, which are otherwise being killed by poachers, and share the returns with the communities, the same animals can become a source of revenue.

This will tend to minimise poaching as the local people will have an incentive in guarding the animals. To do this, hunting licenses can be issued after deciding the sustainable bag limits and other necessary regulations. Licenses can be auctioned annually to the travel agents or hunting outfitters, who can then bring in sport hunters, with all the attendant benefits to the local people. In such a scenario, where more animals means more returns, people will have a built-in incentive for preserving these populations, rather than exterminating them. Apart from generating revenues from hunting fees, it will also support local businesses and employment as outfitters, guides, and in hospitality. The revenues generated from the operations can be used to compensate crop losses as well. Some of our common species, such as black buck, nilgai, sambar, chital and wild pig are eminently suited for this kind of management. Hunting, both for sport and for managing populations, is practiced in most countries of the world. It pays for a major proportion of the conservation budget and brings in very high returns to the adjoining communities. Indian herbivores, introduced abroad are among the most popular trophies in North and South America. Some of the internet advertisements for these animals are shown below as a sample:

1 King Ranch, Texas.

• Nilgai

• $300.00 per gun per day plus harvest fee (1 day hunt).

• Bull $900.00 harvest fee per bull

• Cow $500.00 harvest fee per cow

2 YEAR ROUND TEXAS-LTD HOG HUNTS

• 2 days - $600.00 - 2 hogs.

3 Texas hog hunts, ARCHERY ONLY

• 2 day minimum, 4 hog limit, lodging, tripods and feeders included, $100.00 per day, TROPHY FEE of $350.00

4 South Texas wild hog/javalina hunts, GUARANTEED SHOT

• days / 2 hogs, $395.00,

• day - $500 - 2 Hogs, Deluxe Lodging and Meals

5 Clubs and Associations Specializing in Wild Boar Hunting

Iowa Bowhunters Association

• Michigan Bow Hunters

• North Carolina Outdoor Recreation Club

• Virginia, Blacksburg—Shawnee Hunting Club

6 Texas Safari Ranch (www.texassafari.com)

• Axis - $ 2000

• Black Buck - $1600

7 Argentina Hunting (www.argentinahunting.8m.com)

Official website of Argentina offers hunts for spotted deer, black buck, wild boar and wild buffalo, among others.

Legal Issues

As mentioned at the outset, the WPA, in its current form does not support any population management options. Section 12 gives a very restrictive definition of ‘Scientific management’ of wildlife as ‘translocation of any wild animals to an alternative suitable habitat’ or ‘population management of wildlife without killing or poisoning or destroying any wild animals’. Section 11 (1) (b) of the Act, permits hunting of wild animals belonging to Schedule II, III and IV, if they become dangerous to human life and property, including standing crops. There is a glaring contradiction between these two sections. What section 11 permits us in terms of permitting ‘hunting’ problem populations, section 12 has taken it away by putting serious constraints on the term ‘management’. As we have no expertise in mass translocation of wild animals, we are in no position, at all, to manage our problem populations. However, we can hunt these populations to their extermination without calling it ‘management’ as section 11 permits hunting in all its expressions, such as killing, poisoning and destroying etc. Hunting and translocation are the only tools for scientific management of wildlife. But, while translocation is an emergency response in selected situations, hunting is a routine operation for managing wildlife populations all over the world. By outlawing hunting we have almost totally eliminated any chances of serious attempts at alleviating the suffering of forest dwelling communities.

Scientific management of wildlife is a tool to draw maximum benefits from this resource as well as to minimise the losses due to human wildlife conflict. These benefits can be drawn only through a system of ownership, utilisation and trade of wildlife products such as meat, trophies etc. The WPA does not permit any of these enterprises. Under such circumstances, management of populations, over abundant or not, is irrelevant.

In response to the wide spread hue and cry against crop damage by nilgai, wild pig and black buck, many states, such as UP, MP, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, etc. have permitted their hunting, except black buck, under severe restrictions. Madhya Pradesh has permitted killing of nilgai and wild pig but no one has applied for permission because of impossible and impractical conditions imposed.

Summary of Hunting Systems Permitted in Different States

State Species Features

MP Wild pig Sport hunting outside RF/PF, beyond 5 km from PA boundary, permit issued by SDM, licence fee: local hunter Rs. 100, district level hunter Rs. 1000 per year, royalty: Rs. 100/animal, maximum hunt allowed: 5 animals per license/year

Nilgai Hunting license issued by SDM on complaint, anyone with a licensed weapon can be permitted to hunt, has to hunt in the complainant’s field only, and within 15 days, carcase property of the government.

Rajasthan Nilgai Forest Rangers to DCF authorised to kill, in specified districts

Whereas the legal provisions for hunting animals have been there since the inception of the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, these have never been used due to the belief that any show of utilitarian attitude towards wildlife may trivialize its sanctity. Although the Act was amended in 1991, and again in 2002, to remove provisions for hunting, for pleasure or revenue, the MP Wildlife (Protection) Rules, 1974 still retain the original plan for sport hunting. Same may be true for other states as well.

Sceptics may raise the bogey of political and cultural problems. If the programme is liked and accepted by the people, the politicians will also support it. As far as the so-called cultural aversion to hunting is concerned, it is a complete hoax. A large majority of our people are non-vegetarian, poachers are butchering our wild, shikar was banned only as recently as 1970, while the sleeping provisions for hunting continued right up to 1991. The Madhya Pradesh Wildlife (Protection) Rules, 1974 still contain provisions regarding the constitution of shooting blocks and hunting fees. If fishing can be permitted, why should killing of any other species be a taboo? We can be confident that if a proper communication campaign is launched before such a decision is implemented, we can have sufficient public opinion in favour of a people-centred and scientific wildlife utilization programme. The arguments against sport hunting, given by well-meaning conservationists are as follows:

a) that starting sport hunting may open the floodgates for more poaching in the name of legal hunting;

b) we may not be able to control the bag limits within scientific prescriptions, due to our notorious inability to implement our regulations;

c) it may deplete the prey base for endangered carnivores, and may lead to a rise in cattle-lifting depredations.

These are valid fears but a closer look will show that there are built in answers to these fears. The very proposal for introducing sport hunting is meant to reduce poaching by making entire rural populace the guardians of wild animals, instead of only the forest guard protecting the animals. As far as the question of exceeding sustainable bag limits is concerned, the risk is minimum in view of the fact that if the communities start getting reasonable incomes from the venture, the incentive and pressure to stick to sustainability considerations will be a reasonable safeguard. Conservation lobbies and scientific institutions as independent watchdogs to ensure that limits are not crossed. The fear of depleting the prey base for predators is also unfounded as the numbers to be hunted will be very low (below 5% of the adult population per annum), and that too be compensated by a reduction in poaching. Moreover, experience worldwide shows that, rather than depleting, populations of hunted animals grow, under the influence of properly managed hunting programmes (see box).

WILDLIFE AS A NATURAL RESOURCE

Animal resources, like plant resources, have a natural growth curve, involving growth, equilibrium and decay, in that order. This growth pattern eminently lends itself to human intervention according to scientific principles. If we do not control growing populations, by removing the annual increment at or just before the equilibrium, the animals will destroy their habitat, and consequently themselves. They will also become pests and will, in any case, lose popular and political support. It will neither serve the interests of the protectionists nor of pragmatic conservationists if the populations are permitted to enter the decay phase without any economic benefits to the society. Wildlife, then is viewed as a renewable natural resource and its management as such for human welfare is vital. Experience worldwide has proved this beyond doubt and we should reconsider our ecological policies, as we are revising our economic policies, in the light of global experiences. As nothing can be attempted beyond the prevailing legal framework, we will have to begin by overhauling the WPA to bring it in tune with the principles being followed globally.

Annexure- I

Summary of Compensation Systems in various states

Type of Loss

State

Rate of Compensation (Rs.)

Crop damage

AP

At par with natural calamities or riots.

West Bengal 2500/ha

Bihar 500/acre

Jharkhand 2,500/ha

Meghalaya 3750-7500/ha

Tamil Nadu Up to 15000

Orissa 1000/acre.

Karnataka 2000/acre

UP 150-2500/acre

Gujarat 250-5000

Livestock deaths AP

Market Value

West Bengal 70-450

Meghalaya 100-1500

MP 5000

Jharkhand 500-3,000

Maharashtra 3000-9000

(or 75% of the market value, whichever is less)

Human deaths, Permanent disability, Injuries

Karnataka

25000-100,000

Assam

20,000

UP

5000-50,000

Gujarat

2500-100,000

AP

Up to 20000

W Bengal

5000-20000

Tamil Nadu 20000-10,0000

Bihar 6000-20000

Jharkhand 33,333 -1,00,000

Meghalaya 30,000-100,000

MP 10,000-50,000

Orissa 2,000-1,00,000

Maharashtra 50,000-2,00,000

Loss of house, other property Karnataka 5,000

UP 400-3000

AP At par with natural calamities or riots

West Bengal 500-1000

Bihar 200-1000

Jharkhand 1,000-10,000

Meghalaya 5000-10,000

Tamil Nadu 5000

Orissa 2,000-3,500